The Architecture of InevitabilityThere is a peculiar dissonance in attempting to expand the void. Bryan Bertino’s 2008 original, *The Strangers*, was a masterpiece of nihilism because it refused to answer the question "Why?" Its terror lay in its randomness; the violence was as arbitrary as a lightning strike. Renny Harlin’s ambitious, simultaneously filmed trilogy—concluding now with *Chapter 3*—has spent nearly five hours attempting to fill that void with structure, lore, and conspiracy. The result is a film that is visually muscular and aggressively tense, yet philosophically at war with the very source material it seeks to honor.

Harlin, a director whose career is defined by kinetic energy (*Deep Blue Sea*, *Cliffhanger*), brings a distinct visual polish to the town of Venus, Oregon. Where the previous chapters felt like claustrophobic exercises in endurance, *Chapter 3* opens the aperture. The cinematography captures the Pacific Northwest not just as a setting, but as a trap—a lush, green cage where the silence is heavy with threat. The film’s visual language shifts here from the frantic handheld panic of *Chapter 1* to something more composed and funereal. Harlin stages the violence with a grim precision, moving away from jump scares toward a suffocating sense of dread. The shadows aren't just hiding killers anymore; they seem to be hiding a rot that infects the entire town.

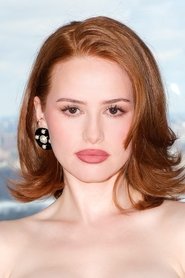

At the center of this maelstrom is Madelaine Petsch’s Maya. If the horror genre often treats its "Final Girls" as disposable scream factories, Petsch demands we witness the cost of survival. Maya is no longer the terrified girlfriend of the first film; she has been hollowed out by trauma and refilled with cold rage. The performance is physical and jagged. There is a sequence near the climax, involving a confrontation with the "Man in the Mask" (Gregory), where the dialogue is sparse, but the emotional transaction is deafening. We watch a human being shed their humanity to survive a monster. It is a tragedy masquerading as a victory.

However, the film stumbles when it tries to rationalize the irrational. *Chapter 3* commits the cardinal sin of explaining the magic trick. By deepening the involvement of side characters like Sheriff Rotter and giving the Strangers a quasi-mythological context within the town, the narrative dilutes the primal fear of the unknown. When "Because you were home" becomes a conspiracy, the Strangers cease to be boogeymen and become mere criminals. The script struggles under the weight of its own expansion, mistaking complication for depth. The terror of the Strangers was that they could be anyone; making them *someone* specific diminishes their power.

Ultimately, *The Strangers: Chapter 3* is a fascinating failure of ambition. It is technically proficient and features a lead performance that transcends the material, yet it fundamentally misunderstands the nature of the fear it toys with. It tries to build a cathedral out of a gravestone. Renny Harlin has delivered a trilogy that is loud, bloody, and undeniably made with craft, but in the end, it proves that some mysteries are more terrifying when left in the dark. We leave the theater not haunted by the inexplicable, but merely exhausted by the explanation.