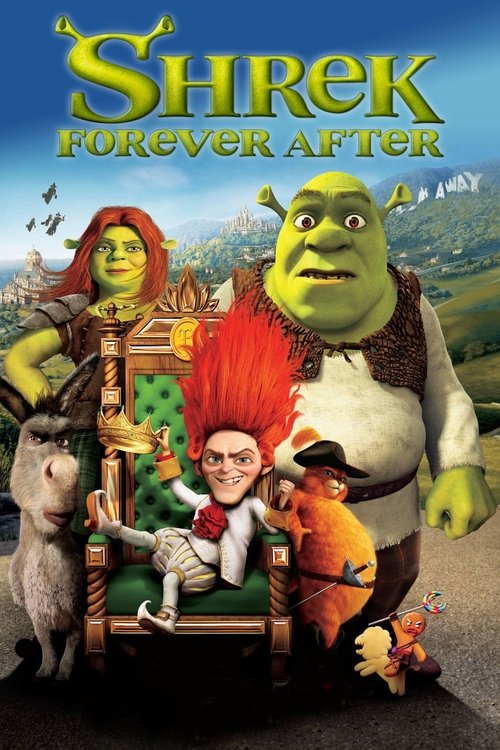

The Ogre in WinterBy 2010, the cultural phenomenon of the green ogre had reached a saturation point. The law of diminishing returns had set in, threatening to reduce a once-subversive fairy tale satire into a mere vehicle for pop-culture references. Yet, *Shrek Forever After* defies the cynicism often reserved for fourth installments. Directed by Mike Mitchell, the film operates less as a victory lap and more as an introspective epilogue. It strips away the noise to examine a surprisingly mature theme: the quiet desperation of domestic stability.

The film opens not with a grand adventure, but with a montage of suffocating routine. Shrek has become a tourist attraction, a domesticated patriarch whose roar is now a party trick requested by bratty children. This is a bold narrative choice for a family film; it acknowledges the "midlife crisis" not as a joke, but as a genuine existential void. Shrek loves his family, yet he feels the phantom limb of his former self—the terrifying outcast who commanded respect, or at least fear. This internal conflict sets the stage for a Faustian bargain with Rumpelstiltskin, a villain who trades not in power, but in regret.

Mitchell’s visual direction shifts drastically once the contract is signed. We are transported from the bright, candy-colored saturation of Far Far Away to a desaturated, dystopian alternate reality. This world is sharper, darker, and genuinely threatening. The witches here are not comic relief but scavengers, and the landscape is barren. This stylistic pivot serves the narrative: by visually draining the life from the world, Mitchell illustrates the void left by Shrek’s absence. It is a world without the ogre's heart, quite literally.

The emotional core of the film, however, lies in its reimagining of Princess Fiona. In this timeline, she is not a damsel waiting to be rescued, nor merely a wife managing a household. She is the war-weary leader of an ogre resistance. This iteration of Fiona forces Shrek—and the audience—to confront the reality that she was never defined by him. Her strength was innate; he simply happened to be the one to witness it in the original timeline. Watching Shrek attempt to woo a woman who views him as a stranger (and a nuisance) deconstructs their romance, forcing him to earn her love through action rather than destiny.

We must also acknowledge the antagonist. Rumpelstiltskin, voiced with manic energy by Walt Dohrn, is a fascinating deviation from the series’ previous villains. He is not a physical threat like the Dragon or a towering figure of authority like the Fairy Godmother. He is a petty bureaucrat of evil, a small man who uses fine print to destroy lives. He represents the danger of nostalgia—the promise that we can go back to "the good old days" if we just sign away our present. His interactions with Shrek are tense not because of physical stakes, but because he holds the mirror up to Shrek’s own ingratitude.

Ultimately, *Shrek Forever After* functions as a *It's a Wonderful Life* for the animated set. It risks alienating younger viewers with its somber tone to deliver a message to the parents in the audience. It argues that "happily ever after" is not a static endpoint, but a daily choice to appreciate the mundane. By the time the sun rises on the final day, the film has justified its existence. It closes the book not with a shout, but with a sigh of relief—a reminder that the greatest adventure isn't slaying the dragon, but finding peace in the quiet moments that follow.