The Rot in the GardenFor decades, Ron Howard has operated as Hollywood’s most reliable humanist. From the buoyant optimism of *Apollo 13* to the sentimental mathematics of *A Beautiful Mind*, his cinema has largely suggested that competence, cooperation, and decency will prevail. This is why *Eden* feels less like a new entry in his filmography and more like a violent defenestration of his previous worldview. Adapting the stranger-than-fiction "Galapagos Affair" of the 1930s, Howard has crafted a survival thriller that is visually muddy, morally repugnant, and fascinatingly cynical. It is a film that argues that if you strip away civilization, you do not find the noble savage; you find the savage ego.

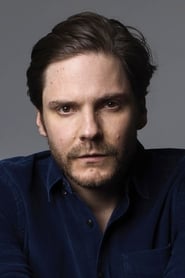

The narrative concerns Dr. Friedrich Ritter (Jude Law) and his acolyte Dore Strauch (Vanessa Kirby), who flee the bourgeois decay of Weimar Germany for the uninhabited island of Floreana. They seek a Nietzschean solitude, a place to forge a "new man" free from society's corruption. But their isolation is pierced, first by the Wittmer family (Daniel Brühl and Sydney Sweeney), who bring the mundane domesticity Ritter despises, and then by the Baroness Eloise Bosquet de Wagner Wehrhorn (Ana de Armas), a self-styled aristocrat who arrives with a revolver, two lovers, and plans for a luxury hotel.

Visually, Howard and cinematographer Mathias Herndl make a bold, somewhat alienating choice. Rather than leaning into the turquoise allure of a travel brochure, *Eden* is suffocated by a palette of slate greys, bruised purples, and dying greens. The camera refuses to romanticize the landscape. The ocean is not a liberating expanse but a prison wall; the jungle is not lush, it is thorny and abrasive. This visual ugliness serves the narrative: this was never a paradise. It was a rock in the ocean onto which desperate people projected their delusions. By stripping the island of its beauty, Howard forces us to look at the ugliness of its inhabitants.

The film’s engine is not the struggle against nature—though the elements are harsh—but the friction of colliding philosophies. Jude Law delivers a performance of grotesque vanity; his Dr. Ritter is a man who loves humanity in the abstract but loathes people in the particular. He is toothless, naked, and endlessly pontificating, a false prophet of his own making. Contrasting him is Ana de Armas’s Baroness, who enters the film with the subtle grace of a hurricane. She is the embodiment of the capitalist hedonism Ritter fled, yet she possesses a chaotic honesty that he lacks. De Armas plays her not just as a villain, but as a disruptive frequency, exposing the hypocrisy of everyone around her.

What makes *Eden* unsettling is how it dismantles the very concept of "starting over." Howard suggests that we cannot leave our baggage at the dock; we carry our social hierarchies and petty jealousies into the wild. The Wittmers, initially the sympathetic "normal" family, slowly devolve under the pressure, with Sydney Sweeney’s Margret transforming from a terrified housewife into a hardened survivalist. The descent is not tragic; it is inevitable. The film posits that hell is not just "other people," as Sartre claimed, but specifically *these* people, trapped in a pressure cooker of their own making.

While the third act arguably stumbles into repetitive cycles of betrayal, losing some of the psychological nuance for shock value, *Eden* remains a gripping exercise in misanthropy. It is jarring to see Ron Howard, the man who once looked at the stars with such hope, look down into the dirt and see only rot. This is not a film about the triumph of the human spirit; it is a film about the triumph of the human ego, and how it can turn even the most pristine garden into a graveyard.