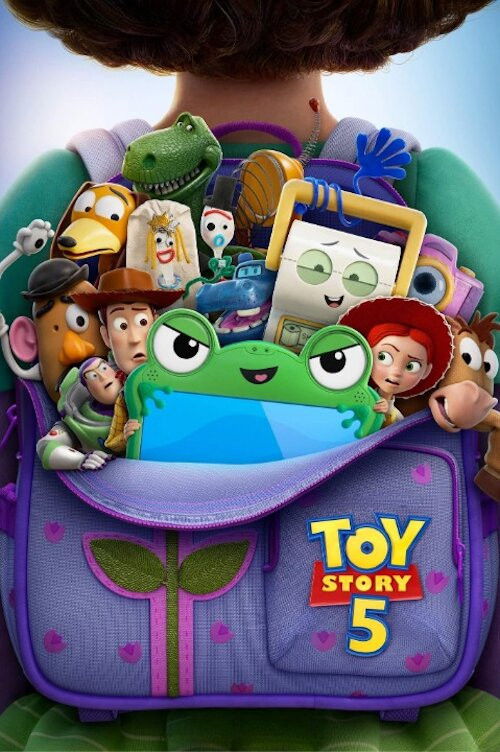

The Obsolescence of InnocenceIn the thirty years since Pixar first convinced us that a cowboy doll had a soul, the studio has returned to the well four times, each visit fraught with the diminishing returns of nostalgia. Yet, *Toy Story 5* arrives not as a cash grab, but as a surprisingly melancholy meditation on attention in the digital age. Directed by Andrew Stanton—the architect of *WALL-E*’s silent despair—this fifth installment abandons the "road trip" structure of its predecessor for something more claustrophobic and culturally resonant. It is a film that asks a brutal question: What happens to imagination when the screen does the imagining for you?

Stanton’s visual language here is distinct from the warm, sun-drenched antiques shop of *Toy Story 4*. The cinematography leans into the cool, blue-light sterile glow of LED screens. The film’s opening act establishes a new visual hierarchy in Bonnie’s room. The toys are no longer scattered in joyful chaos; they are neatly shelved, collecting dust in the shadows, while the center of the frame is dominated by "Lilypad," a frog-shaped tablet voiced with terrifyingly cheerful condescension by Greta Lee.

The brilliance of Stanton’s approach lies in how he frames the "villain." Lilypad isn't evil in the mustache-twirling tradition of Lotso or Stinky Pete. She is simply *engaging*. The conflict isn’t physical; it is attentional. The film visualizes the toys’ obsolescence through a heartbreaking sequence where Woody and Jessie attempt to stage a rescue mission for a "lost" toy, only to realize Bonnie hasn't lost it—she has simply scrolled past it. The animation during these moments is staggering; the texture of the plastic feels more brittle, more aged, contrasting sharply with the frictionless, high-definition gloss of the tablet’s interface.

However, the film’s stroke of genius—and its primary source of kinetic energy—is the subplot involving the army of fifty malfunctioning Buzz Lightyears. By introducing a platoon of commemorative figures stuck in "demo mode," Stanton satirizes the franchise’s own commodification. These aren’t characters; they are "content," identical and hollow. Watching the original Buzz (Tim Allen, delivering his most weary and nuanced performance yet) confront this legion of unthinking duplicates offers a profound commentary on identity. It’s a literalization of the struggle to remain an individual in an algorithmically generated world.

The emotional core, inevitably, rests with Tom Hanks’ Woody. Having returned from his "lost toy" sabbatical (a narrative leap the script handles with surprising grace), Woody is no longer the frantic manager of Andy’s room. He is an elder statesman facing the final frontier: irrelevance. The script avoids the easy "technology is bad" moralizing one might fear. Instead, it suggests a synthesis. The climax doesn’t involve smashing the tablet, but rather finding a way for the tactile and the digital to coexist. It’s a messy resolution, perhaps less emotionally precise than the incinerator scene of *Toy Story 3*, but far more honest about the reality of modern childhood.

*Toy Story 5* justifies its existence by maturing with its audience. It is no longer just about the fear of being outgrown; it is about the fear of being replaced by something that doesn't love back. It is a film that argues, quite movingly, that while a screen can provide endless entertainment, it cannot offer the one thing a toy can: companionship. In an era of infinite distraction, Stanton reminds us that the most radical act is simply being present for someone else.