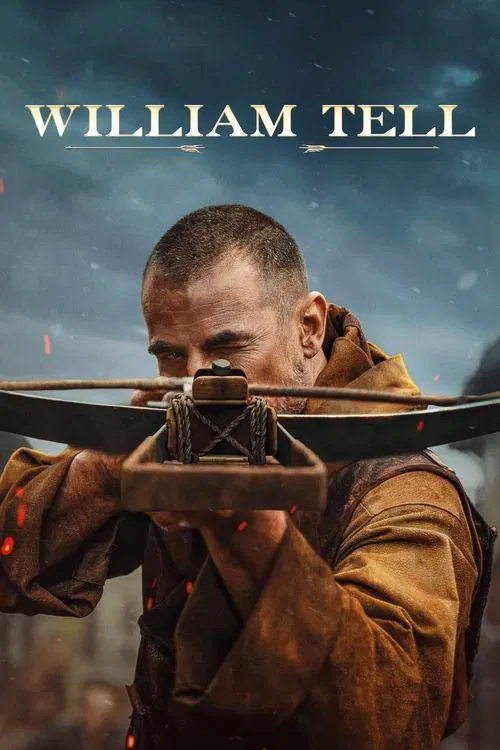

The Arrow and the AbyssIn the modern cinematic landscape, the "historical epic" has become an endangered species, often replaced by fantasy franchises where dragons, rather than despots, burn down villages. Director Nick Hamm’s *William Tell* attempts to resurrect this dormant beast, stripping away the operatic whimsy often associated with its titular hero (thanks, Rossini) to reveal a grim, muddy parable about the cost of pacifism in a world demanding blood. It is a film that yearns to be *Braveheart* for a more cynical age, yet it often finds itself caught between the gravity of its themes and the inertia of its own solemnity.

Visually, Hamm and cinematographer Jamie D. Ramsay treat the Swiss Alps not as a postcard, but as a prison of granite and ice. The film’s aesthetic is relentlessly desaturated, favoring the greys of chainmail and the whites of unforgiving snow over the lush greens one might expect. This choice serves the narrative well; the landscape feels ancient and indifferent to the human suffering played out upon it. The violence, when it erupts, is sudden and unglamorous—limbs are severed and arrows find their marks with sickening crunches. Hamm aims to ground the myth in dirt, removing the shiny veneer of legend to show us a 14th-century insurgency that looks uncomfortably like modern guerrilla warfare.

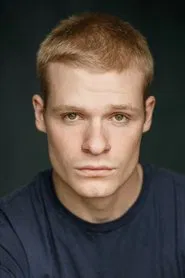

At the center of this frozen storm is Claes Bang, an actor of immense physical presence who plays Tell not as a swashbuckling hero, but as a man hollowed out by trauma. The script reinvents Tell as a weary veteran of the Crusades, a man who has seen enough of "God’s work" to know it usually involves slaughter. Bang’s performance is one of interiority; he speaks in low rumbles, his eyes constantly scanning the perimeter for threats. He is a reluctant messiah, a man who just wants to farm his land but is dragged back into the abyss by the sadistic Austrian bailiff Gessler (played with reptilian glee by Connor Swindells). The tension between Tell’s desire for anonymity and history’s demand for a hero is the film’s most compelling engine.

However, the film stumbles when it tries to widen its scope beyond Tell’s personal vendetta. The screenplay, adapted from Friedrich Schiller’s play, struggles to balance the intimate tension of the famous apple-shot scene with the sprawling geopolitical machinations of the Holy Roman Empire. The iconic moment itself—where Tell must shoot the apple from his son’s head—is staged with nerve-shredding precision, a masterclass in editing and silence. Yet, the surrounding political drama, involving a rotisserie of Habsburg villains including a strangely underutilized Ben Kingsley, often feels like checking boxes on a "prestige drama" list. We understand the tyranny, but the film sometimes forgets to make us feel the specific pulse of the rebellion, relying instead on broad speeches about freedom that echo a bit too familiarly of Hollywood’s past.

Ultimately, *William Tell* is a sturdy, if somber, piece of filmmaking that respects the intelligence of its audience even while falling short of greatness. It posits that the true weight of heroism isn't the glory of the shot, but the terror of the aim. It may not reinvent the historical epic, but in Claes Bang’s haunted gaze, it finds a human anchor for a legend that has too often been reduced to a cartoon. It reminds us that before the overture and the applause, there was just a terrified father holding a crossbow, praying he wouldn't miss.