✦ AI-generated review

The Smiling Face of the Abyss

There is a distinct, unsettling danger in giving a monster a microphone, let alone a therapist. In James Vanderbilt’s *Nuremberg* (2025), the courtroom—often the sanitized stage of history’s moral victories—is secondary to the claustrophobia of a prison cell. Here, the struggle is not just legal, but psychological, waged in the quiet, dusty corners of 1945 Germany. Vanderbilt, known for his obsession with the procedural grinding of truth in *Zodiac*, attempts to dissect the Nazi mind not with a scalpel, but with a conversation. The result is a film that is terrifyingly intimate, occasionally tonally confused, but ultimately anchored by a performance from Russell Crowe that sucks the air out of the room.

The film operates on a visual frequency of suffocating gray. Cinematographer Dariusz Wolski paints the aftermath of the Third Reich in sepia-toned exhaustion; the rubble is piled high, but the true ruins are the men waiting to hang. Vanderbilt juxtaposes this grim reality with the shocking theatricality of Hermann Göring’s surrender. We do not meet Göring cowering in a bunker; we meet him in a pristine white uniform, luggage in tow, surrendering with the pomp of a visiting dignitary. This visual contradiction sets the stage for the film’s central thesis: evil does not always look like a nightmare. Sometimes, it looks like a charming, corpulent man making jokes in a cell.

At the heart of this psychological duel is the dynamic between Crowe’s Göring and Rami Malek’s Dr. Douglas Kelley. Malek, playing the American psychiatrist tasked with determining the defendants' fitness for trial, brings a frantic, squirrelly energy to the role. He is the audience surrogate, initially confident in his moral superiority, only to find himself disarmed by Göring’s charisma. And it is Crowe who is the film’s gravitational center. Physically transforming into a figure of Brando-esque mass, Crowe plays Göring not as a frothing antisemite, but as a narcissist of high intellect. He is affable, witty, and deeply manipulative. The terror of *Nuremberg* lies in those moments when you, the viewer, find yourself almost smiling at Göring’s banter, before the cold reality of his crimes crashes back in—a discomforting reminder of how fascism rises on the back of personality, not just policy.

However, the film’s ambition occasionally collapses under the weight of its own "watchability." In its drive to be an engaging psychological thriller, *Nuremberg* sometimes drifts into the uncanny valley of entertainment. There are moments of snappy dialogue and "pep" that feel discordant with the gravity of the Holocaust, a tonal whiplash that critics have rightly noted feels almost like "Marvel-esque" banter in a death camp. When Vanderbilt cuts to actual, harrowing archival footage of the concentration camps, the shift is jarring—a brutal reality check that exposes the artifice of the scenes that preceded it. It forces us to question whether a narrative film can ever truly capture such enormity without trivializing it through the lens of a "buddy drama" between a doctor and a war criminal.

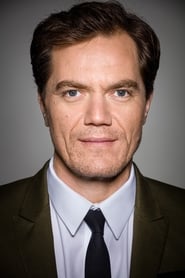

Yet, despite these stumbles, the film lands a potent blow in its final act, particularly through Michael Shannon’s steely performance as Prosecutor Robert H. Jackson. The cross-examination scene is a masterclass in stripping away the mask. When the charm fades and the "banality of evil" is left exposed, we are left with a chilling reflection of our own modern political landscape—where rhetoric and showmanship often obscure the machinery of hate. *Nuremberg* is an imperfect history lesson, but as a study of the seductive power of a demagogue, it is alarmingly present.