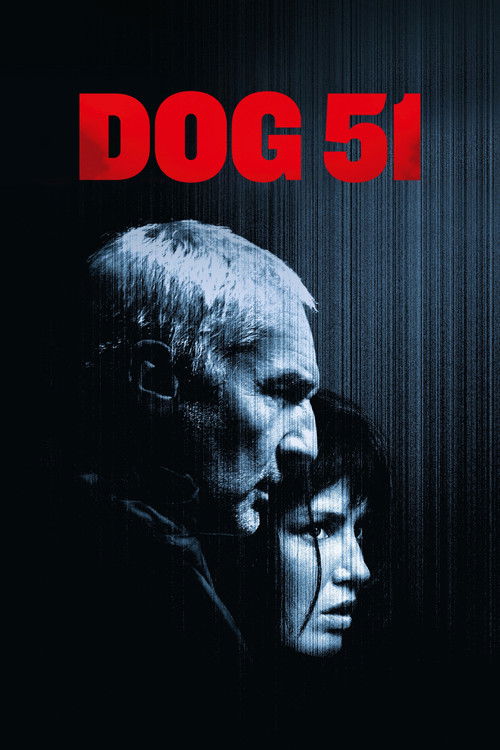

The Architecture of ObsolescenceTo watch a Cédric Jimenez film is usually to witness the muscular spasms of the French state. In *Bac Nord* and *Novembre*, he chronicled the frantic, often brutal reality of modern policing with a docu-drama urgency that felt ripped from the headlines. With *Dog 51* (or *Chien 51*), Jimenez trades the headlines for the horizon, adapting Laurent Gaudé’s novel into a dystopian noir set in 2045. Yet, despite the sci-fi trappings—predictive AI, social apartheid, and brutalist skylines—the director hasn’t actually left the present. He has simply amplified it. This is not a vision of what might happen; it is a stylized, suffocating portrait of what is already happening, merely dressed in the rain-slicked trench coat of *Blade Runner*.

Visually, Jimenez constructs a Paris that has been anatomically dissected. The city is no longer a cohesive whole but a tiered cage, separated into three zones of escalating privilege and decay. The camera, restless and prowling, thrives in this geography. Jimenez and cinematographer Laurent Tangy treat the setting not as a backdrop but as an antagonist. The Zone 3 slums are rendered in claustrophobic shadows and sodium-vapor yellows, a sharp contrast to the antiseptic, terrifying cleanliness of Zone 1. The visual language here is kinetic and oppressive; drone shots swoop down like birds of prey, mimicking the gaze of ALMA, the omnipresent AI that now dictates the law. The film achieves a suffocating sense of reality where the CGI enhances, rather than replaces, the grit. You can practically smell the ozone and wet concrete.

At the center of this architectural nightmare are two relics trying to solve a murder that the machine failed to predict. Gilles Lellouche plays Zem, a Zone 3 cop who wears his exhaustion like a second skin. Lellouche, a Jimenez regular, excels at playing men who are physically imposing but spiritually hollowed out. He is paired with Salia (Adèle Exarchopoulos), an elite agent from the upper zones who initially trusts the system that Zem despises.

The film’s heart beats in the friction between these two performers. This isn't just a "buddy cop" dynamic; it is a collision of worldviews. Exarchopoulos brings a ferocious, vibrating intensity to Salia, a woman slowly realizing that the algorithm she serves is not a shield, but a shackle. There is a quiet tragedy in their investigation—not in the "whodunit" of the plot, which admittedly follows familiar noir beats—but in their realization of their own obsolescence. They are humans trying to find a human reason for murder in a world that wants to reduce crime to a data point. The "karaoke scene," which could have played as awkward comic relief, instead lands as a desperate, jarring cry for connection in a city that has forgotten how to sing.

Ultimately, *Dog 51* suffers slightly from the weight of its own armor. The script occasionally favors momentum over nuance, flattening some of the novel’s deeper philosophical questions about memory and redemption into standard thriller beats. However, as a piece of sensory cinema, it is undeniable. Jimenez proves once again that he is the master of French "muscle" cinema, orchestrating chaos with a conductor's precision. The film suggests that while technology may change the architecture of our oppression, the human capacity to resist it—messy, analog, and irrational—remains our only hope. It is a bleak warning, delivered at breakneck speed.