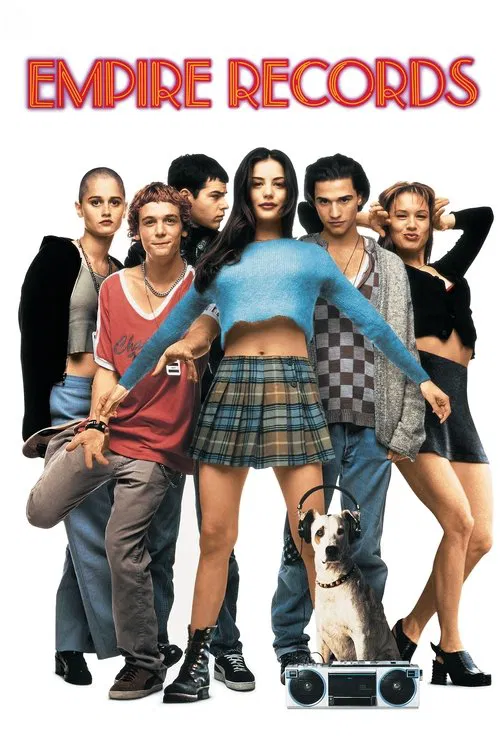

The Last Sanctuary of NoiseTo view Allan Moyle’s *Empire Records* (1995) through the lens of traditional narrative structure is to miss the point entirely. Upon its initial release, critics dismantled the film for its episodic looseness and thin plotting, failing to recognize that Moyle—who had already tapped into the teenage frequency with *Pump Up the Volume*—was not trying to tell a story so much as capture a vibration. This is not a film about a failing business; it is an elegy for the analog age, a preserved insect in the amber of the mid-90s, where the greatest existential threat to youth was not climate change or digital surveillance, but the terrifying concept of "selling out."

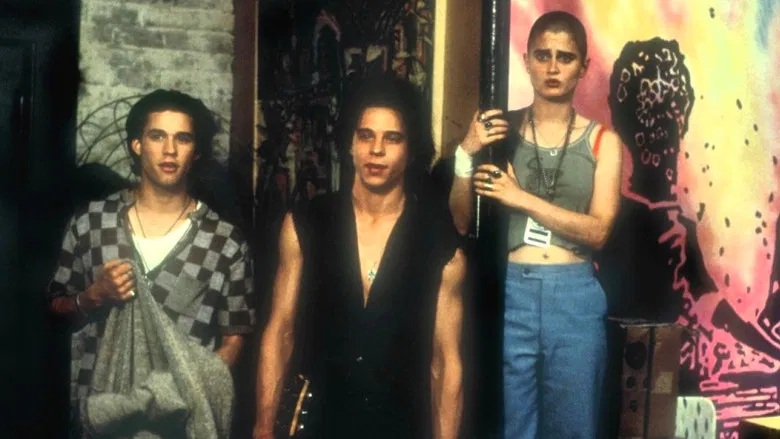

The film operates as a theatrical chamber piece, confined almost entirely to the sticker-covered, neon-lit walls of an independent Delaware record store. Moyle’s camera treats the space not as a retail environment, but as a sanctuary for the socially displaced. The store is a cluttered, chaotic womb where the employees—a motley crew of misfits including the Harvard-bound virgin Corey (Liv Tyler), the amphetamine-addled philosopher Lucas (Rory Cochrane), and the exhibitionist Gina (Renée Zellweger)—can delay the onset of adulthood. The visual language is busy and textured, mirroring the grunge aesthetic of the era: flannel, combat boots, and an overwhelming amount of physical media that serves as the characters' armor against the outside world.

The central conflict is ostensibly financial—Lucas gambles away the store’s daily take in a misguided attempt to save it from being absorbed by "Music Town," a sterile corporate chain. However, the true antagonist is the homogeneity of adulthood. The looming threat of Music Town represents the sanitization of culture, a force that demands employees trim their hair and adhere to strict dress codes. In this context, the film’s villain isn’t a person, but the encroaching inevitability of the monoculture. The arrival of Rex Manning (Maxwell Caulfield), a washed-up 80s heartthrob, serves as a grotesque warning of what happens when art is entirely commodified. Manning is a man comprised of spray tan and sadness, a ghost of pop culture past who the youth mock, even as they secretly fear becoming him.

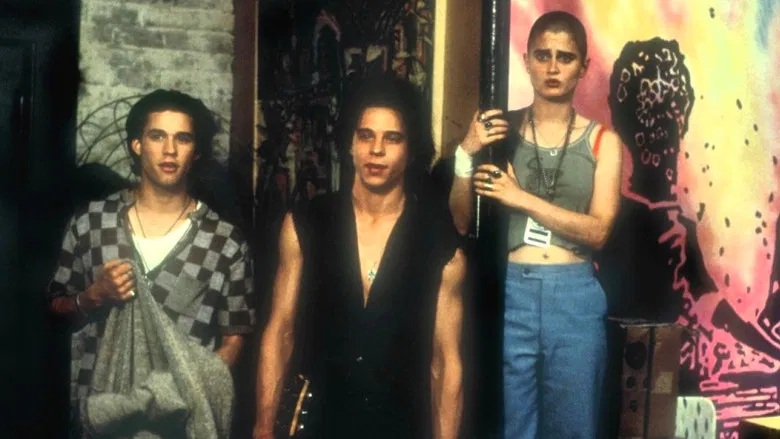

Yet, beneath the sarcasm and the soundtrack-driven interludes, *Empire Records* harbors a surprising tenderness toward its damaged characters. It refuses to mock their pain, no matter how performative it may seem. When Deb (Robin Tunney) shaves her head in a moment of overwhelmed despair, the film does not play it for shock value but treats it as a genuine cry for help, met immediately with a mock funeral that turns into a collective embrace. Moyle understands that for these characters, the record store is the only place where their eccentricities are not just tolerated, but required. The dialogue, often criticized as quippy or unrealistic, functions as a protective shell; when Gina purrs, "Shock me, shock me, shock me with that deviant behavior," she is using irony to deflect from her own vulnerability.

Decades later, *Empire Records* endures not because it is a masterpiece of cinema, but because it is a masterpiece of feeling. It represents a specific cultural moment when the "alternative" label still held a promise of resistance. Watching it today feels like visiting a historical reenactment of a time when we believed that if we just played the music loud enough, we could keep the real world at bay. It is a film that argues, with charming naivety, that a community of friends and a good song are enough to save your soul—or at least, save the store.