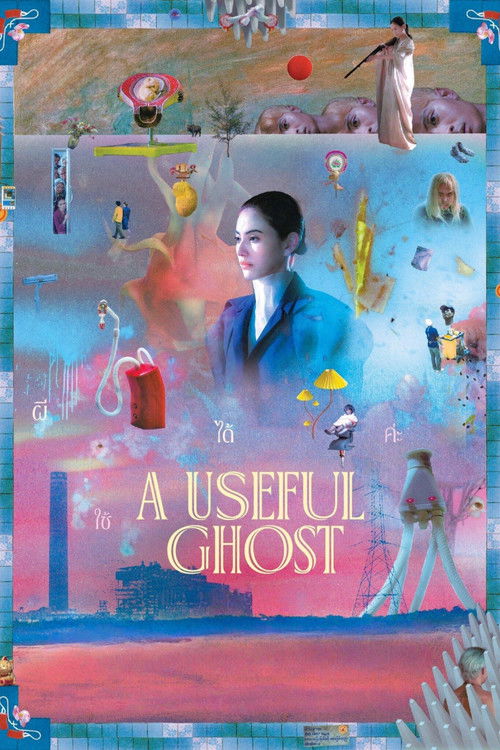

The Dust of HistoryIf there is a defining image of our suffocating modern era, it might just be the humble vacuum cleaner. In Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke’s startlingly original debut *A Useful Ghost*, this mundane appliance becomes a vessel for grief, a tool of political erasure, and—most improbably—the romantic lead in a film that defies every classification it invites. Boonbunchachoke, previously known for his sharp, cerebral short films, has arrived on the world stage not with a shout, but with the wheezing hum of a motor, delivering a "ghost story" that is less about the afterlife and more about the crushing requirements of the present life.

The premise reads like a fever dream or a dark joke shared in a Bangkok café: Nat (Davika Hoorne), a young woman, dies from a respiratory illness caused by the city’s chronic pollution. Unable to leave her grieving husband, March (Witsarut Himmarat), she possesses a red-and-white vacuum cleaner. But this is not the whimsical magical realism of Disney; it is a rigid, bureaucratic nightmare. In Boonbunchachoke’s vision, even the dead must be productive members of society. To avoid exorcism by her wealthy, disapproval mother-in-law, Nat must prove her "usefulness" by sucking up "useless" spirits haunting the family factory.

Visually, the film is a masterclass in static restraint. Working with cinematographer Pasit Tandaechanurat, Boonbunchachoke frames his characters in tableau shots that feel stiflingly composed, mirroring the social cage they inhabit. The "performance" of the vacuum cleaner is a marvel of practical effects—its awkward, jerky movements convey a pathetic desperation that CGI could never achieve. When March caresses the plastic casing of the machine, the scene teeters on the edge of the ridiculous before plunging into profound melancholy. We are watching a man try to love a product because the human being inside it has been consumed by the system.

The "conversation" surrounding this film has rightly focused on its political subtext. The pervasive dust in the film is not merely atmospheric; it is the physical residue of demolished memories. The director explicitly links the particulate matter clogging the characters' lungs to the erasure of Thailand’s political history—the monuments torn down, the protests silenced, the "dust" of the marginalized swept away in the name of progress. A chilling recurring mantra, "There is no progress without dust," uttered by a televised official, serves as the film’s thesis. The vacuum cleaner, then, becomes a tool of complicity. To stay "alive," Nat must help the oppressors clean up the mess of their own exploitation.

Yet, the film’s heart beats loudest in its quieter, queer-coded margins. The narrative is framed by a "Academic Ladyboy" and a handsome repairman, whose interactions provide a Greek chorus to the central absurdity. Boonbunchachoke uses these characters to highlight the conditional acceptance of the "other." Just as the ghost is tolerated only as long as she cleans, the queer characters exist in a precarious state of utility. The tragedy of Nat is that she accepts her dehumanization (or rather, de-personification) for love. She sucks up the "bad" ghosts—perhaps spirits of past laborers or revolutionaries—effectively acting as a class traitor to secure her place in her husband's home.

*A Useful Ghost* is a difficult, prickly film that refuses to offer the catharsis of a traditional ghost story. There are no jump scares, only the creeping horror of a world where value is determined solely by output. It suggests that in late-stage capitalism, we are all ghosts in the machine, frantically trying to prove we are worth the space we occupy. Boonbunchachoke has crafted a debut that is as hilarious as it is devastating, forcing us to ask: when the air clears and the dust settles, who is holding the handle, and who is trapped in the bag?