The Silence of the Lambs (and the Lions)If the first *Raat Akeli Hai* (2020) was a claustrophobic chamber piece about the rot within a single family, its 2025 sequel, *Raat Akeli Hai: The Bansal Murders*, attempts to map that rot onto the anatomy of a city. Director Honey Trehan returns to the dusty, deceit-laden badlands of the Indian hinterland, bringing with him the idiosyncratic Inspector Jatil Yadav (Nawazuddin Siddiqui). But where the first film felt like a sharp, sudden stab in the dark, this sequel operates more like a slow-acting poison—ambitious and sprawling, yet occasionally diluted by its own scope. It is a film that asks not just who killed the Bansal family, but what kind of society requires such a sacrifice to correct its moral equilibrium.

Trehan’s visual language has evolved from the intimate noir of the predecessor into something colder and more forensic. The cinematography captures the Bansal mansion not as a home, but as a mausoleum of wealth, bathed in sterile whites and suffocating shadows. The camera lingers uncomfortably on the aftermath of violence—a family slaughtered in their sleep—forcing the audience to confront the brutality without the safety net of stylization. This is not the glossy violence of a blockbuster; it is messy, ugly, and quiet. The sound design complements this, stripping away the melodramatic score in favor of an oppressive silence, broken only by the cawing of crows or the sterile hum of forensic equipment. It is in these quiet moments that the film screams the loudest.

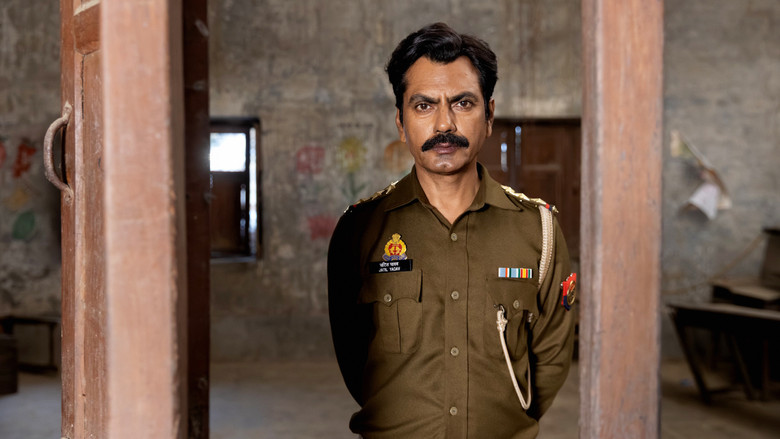

At the center of this grim tableau is Siddiqui’s Jatil Yadav, a performance of remarkable restraint. Jatil is no longer the insecure man hiding his complexion cream; he is wearier, a man who has stared into the abyss long enough to know it’s staring back. Siddiqui plays him with a simmering stillness, his eyes darting around the grandeur of the Bansal estate with a mix of awe and disgust. The film wisely pairs him with Dr. Panicker (Revathi), a forensic expert whose clinical detachment acts as a foil to Jatil’s instinctive policing. Their interplay is the film's intellectual engine, dissecting not just bodies, but the lies the living tell themselves.

The narrative, however, occasionally buckles under the weight of its social commentary. By introducing elements of media sensationalism and a cryptic godwoman (Deepti Naval), the script stretches its murder-mystery skeleton to near breaking point. The "eat-the-rich" thematic undercurrent—where the victims are almost too detestable to mourn—risks robbing the tragedy of its human stakes. Yet, Trehan manages to pull it back in the final act, revealing that the true horror isn't the murder itself, but the systemic complicity that made it inevitable. The introduction of Meera (Chitrangada Singh) adds a layer of tragic elegance, a character who wears her trauma like a shield, challenging Jatil’s perceptions of victimhood.

Ultimately, *Raat Akeli Hai: The Bansal Murders* is a worthy, if imperfect, successor. It trades the tight, Agatha Christie-esque structure of the original for a broader sociological critique. It doesn't offer the easy catharsis of justice served; instead, it leaves us with the unsettling realization that in a world governed by power and privilege, the truth is often just another commodity to be buried. It is a film that suggests the night is indeed lonely, but the darkness is crowded with ghosts we refuse to acknowledge.