The Geometry of ComfortThere is a specific texture to a Nancy Meyers film, a tactile quality that transcends the celluloid. It is the feeling of heavy cashmere, the sound of ice settling into a crystal tumbler, and the soothing symmetry of a kitchen island that costs more than a mid-sized sedan. In *The Holiday* (2006), Meyers deploys this aesthetic not merely as set dressing, but as a narrative device—a high-thread-count safety net for two women free-falling through emotional vertigo. While often dismissed on its release as confectionary fluff, the film has calcified into a modern classic because it understands a fundamental truth: sometimes, a change of scenery is the only way to see oneself clearly.

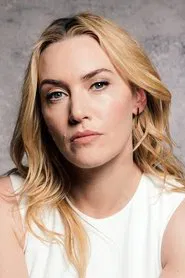

The premise is a masterclass in aspirational escapism. Iris (Kate Winslet), a weepy British columnist trapped in unrequited adoration for a toxic colleague, and Amanda (Cameron Diaz), a neurotic Los Angeles trailer editor who cannot cry, agree to a house swap to escape their Christmas blues. Meyers’ visual language here is distinct. She creates two competing fantasies: the English cottage, a cluttered womb of fireplaces and wool, and the California mansion, a temple of automated blinds and beige minimalism.

Visually, Meyers frames these environments as extensions of the women’s internal states. Iris’s cottage is charming but suffocatingly small, mirroring her inability to grow past her ex. Amanda’s mansion is expansive but sterile, reflecting her emotional unavailability. The brilliance of the film’s "lens" is how the directors of photography (Dean Cundey) light these spaces once the women swap. Amanda brings a brash, American kinetic energy to the sleepy Surrey snow, while Iris is bathed in the golden, therapeutic glow of the California sun. The environments do not just house the characters; they heal them.

However, the film’s enduring heartbeat lies not in the romances, but in the concept of the "meet-cute" with one’s own agency. While the Diaz-Law storyline relies heavily on chemistry and the absurdity of Jude Law as a weeping, widowed father (a fantasy so potent it borders on science fiction), the Winslet storyline offers the film’s true emotional ballast.

Iris’s relationship with Arthur Abbott (the late, great Eli Wallach) remains one of the most tender platonic loves in the rom-com canon. Wallach, playing a relic of Hollywood’s Golden Age, serves as the narrative’s conscience. When he tells Iris she is behaving like the "best friend" in her own life rather than the "leading lady," the film transcends its genre trappings. It stops being about finding a man and becomes a story about finding a spine. The romance with Miles (Jack Black, playing against type with delightful warmth) is almost secondary to Iris falling in love with her own potential.

Ultimately, *The Holiday* survives the cynicism of modern cinema because it refuses to be ironic about loneliness. It treats the pain of heartbreak with the same seriousness as it treats the joy of a perfect fettuccine alfredo. It is a film that argues comfort—physical, emotional, and environmental—is not a luxury, but a necessity for healing. In a world that often demands grit, Meyers offers a radical proposition: that we are allowed to be soft, we are allowed to be warm, and we are allowed to go home.