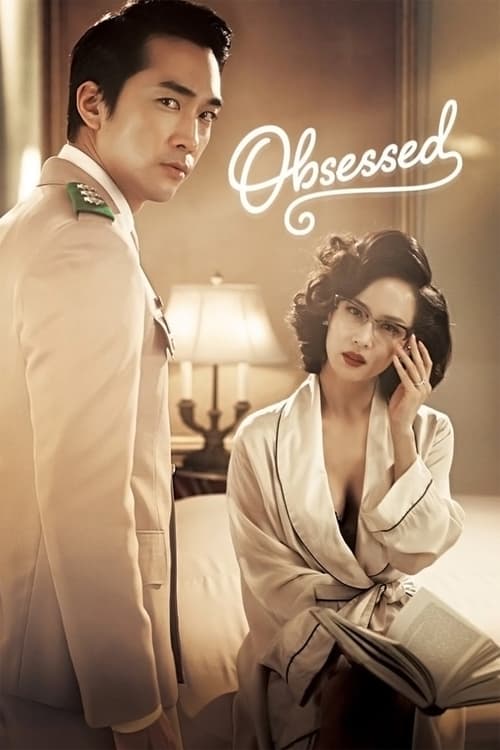

The Architecture of RepressionDirector Kim Dae-woo has spent his career examining the corset of Korean society—usually the literal corsets of the Joseon Dynasty in films like *The Servant* or *Forbidden Quest*. In *Obsessed* (2014), he trades the hanok for the mid-century modern austerity of a 1969 military base, but the thematic architecture remains identical: a rigid, suffocating social hierarchy that makes human passion not just taboo, but treasonous.

The film is often categorized reductively as an "erotic thriller," a label that does a disservice to its suffocating atmospheric dread. This is not a film about sex as pleasure; it is a film about sex as the only available oxygen. Colonel Kim Jin-pyeong (played with a bruised stoicism by Song Seung-heon) is a Vietnam War hero returning to a hero’s welcome that feels more like a funeral. He is a man hollowed out by PTSD, trapped in a "perfect" marriage that operates with the cold efficiency of a military drill.

Kim Dae-woo’s visual language here is immaculate and deliberate. The cinematography captures the military housing complex as a manicured prison. The lawns are too green; the wives’ tea parties are too polite; the uniforms are too crisp. Into this sterile environment steps Jong Ga-heun (Lim Ji-yeon, in a haunting debut performance), the wife of a fawning subordinate. She is a disruption not because she is loud, but because she is almost spectrally quiet.

The director uses this silence as a weapon. The chemistry between Jin-pyeong and Ga-heun isn't built on witty banter, but on shared trauma. They recognize in each other a mutual alienation. When Jin-pyeong suffers a flashback or a panic attack, the camera tightens, trapping us in his headspace, making the affair that follows feel less like adultery and more like a desperate attempt to feel something other than fear. The "obsession" of the title (originally *Inganjungdok* or "Human Addiction") suggests that for these two, the affair is a narcotic to numb the pain of their prescribed roles.

However, the film is not without its structural fractures. While the first two acts are a masterclass in tension—using the birdcage metaphor to perhaps slightly obvious but effective ends—the third act collapses under the weight of traditional melodrama. The film abandons its psychological nuance for operatic gestures that feel jarring against the quiet intensity that came before. The pivot from repressed longing to explosive, public confrontation undoes some of the delicate work done by the actors, forcing them into a climax that feels written rather than earned.

Lim Ji-yeon deserves specific praise for grounding this narrative. Her character could easily have been a femme fatale caricature, but she plays Ga-heun with a clipped-wing vulnerability that makes her reticence magnetic. She is the ghost in the machine of this military industrial complex.

Ultimately, *Obsessed* is a film that succeeds more as a mood piece than a narrative triumph. It is a stunningly photographed portrait of how the Vietnam War cast a long, silent shadow over Korean domestic life, turning homes into battlefields of their own. It suggests that in a world demanding absolute order, the only act of freedom left is to destroy oneself through love.