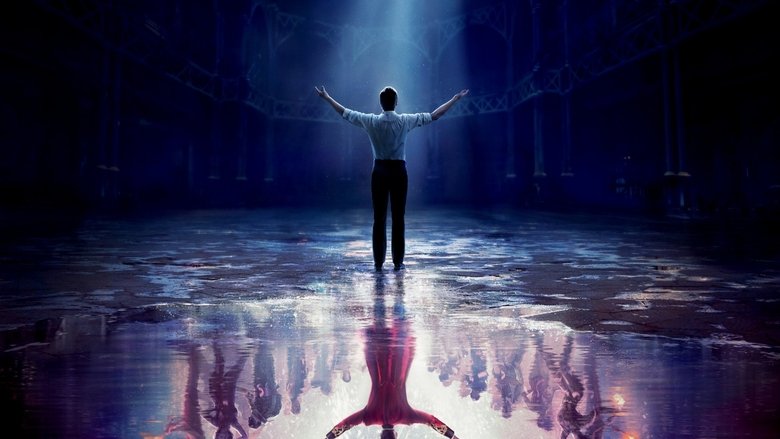

The Greatest Lie Ever ToldHistory has a way of smoothing its own rough edges, but few films have ever taken a belt sander to the truth quite like Michael Gracey’s *The Greatest Showman* (2017). Ostensibly a biography of P.T. Barnum, the 19th-century circus impresario and master of the "humbug," the film arrives not as a historical document but as a fever dream of pop-timism. It is a spectacle of blinding color and deafening joy that asks us to forget that its hero was, in reality, a complicated figure often trafficking in exploitation. Yet, to dismiss Gracey’s debut merely for its historical amnesia is to miss the point of its existence. This is not a film about P.T. Barnum, the man; it is a film about the *idea* of the show, a meta-commentary on the very lie cinema sells us: that if you sing loud enough, the darkness simply disappears.

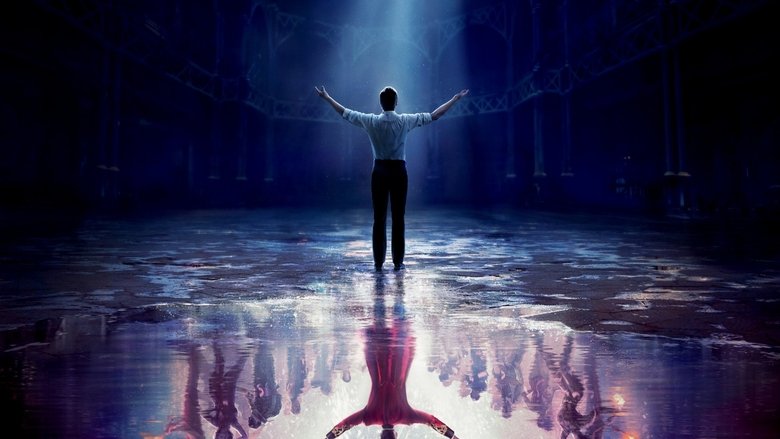

Gracey, emerging from the world of commercials and music videos, creates a visual language that is aggressively anachronistic. He rejects the dusty sepia tones of the traditional period piece in favor of a Baz Luhrmann-esque hyper-reality. The 1800s here are merely a costume; the soul of the film is pure, modern pop. The cinematography is restless, swirling around Hugh Jackman’s Barnum with the kinetic energy of a stadium concert. Scenes transition not through narrative logic but through the emotional beats of Benj Pasek and Justin Paul’s earworm songs. The reality of the film is a soundstage reality, artificial and proud of it. When Barnum and his troupe dance, the world around them often fades into stylized backdrops or rhythmic editing, suggesting that the "Greatest Show" isn't the circus itself, but the shared delusion of happiness they are constructing together.

At the heart of this candy-colored storm is a friction between the script's intent and its subtext. The narrative frames Barnum as a champion of the marginalized, a man who gave "oddities" a home. Jackman plays him with such earnest, megawatt charisma that we almost believe it. However, the film's true emotional weight rests not on Barnum, but on the "freaks" he employs. The anthem "This Is Me," led by the bearded lady Lettie Lutz (Keala Settle), serves as the film’s emotional anchor. It is a scene of profound defiance—not just against the fictional mobs within the movie, but against the very industry that usually sidelines such performers. Here, the film transcends its own sanitized history. For three minutes, the "content" fades, and we witness a raw, guttural cry for visibility that feels painfully relevant to the modern outcast. It is a moment of pure cinematic empathy that almost absolves the film of its narrative sins.

Ultimately, *The Greatest Showman* succeeds by functioning exactly like a P.T. Barnum exhibit: it is a beautiful fraud. It invites us to be hoodwinked, to suspend our cynicism and buy into a fantasy where class struggles are solved with a handshake and racial tensions melt away on a trapeze. It is a film that demands we look at the surface, not the depth. In an era of gritty reboots and dark character studies, Gracey’s film is a defiant, uncool assertion that sometimes, we don't go to the movies to see the world as it is, but as we wish it could be—bright, loud, and gloriously fake.