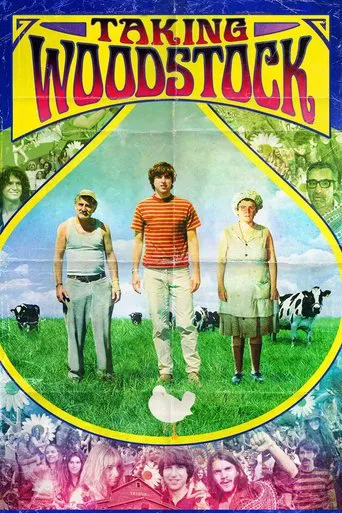

The Geometry of Childhood FearTo dismiss Andy Muschietti’s *It* (2017) as merely another entry in the recent deluge of Stephen King adaptations is to misunderstand its fundamental aim. While it wears the trappings of a summer blockbuster—jump scares, a shapeshifting antagonist, and a band of misfit heroes—the film operates on a frequency far more melancholic than its genre peers. This is not simply a creature feature; it is a bruised, tender elegy for the death of innocence, examining how the traumas inflicted by the adult world manifest as monsters in the minds of the young.

Muschietti, taking the reins of a property burdened by the iconic legacy of Tim Curry’s 1990 performance, wisely chooses to pivot the terror inward. If the earlier iteration was a campy nightmare, this version is a grim fairy tale. The director understands that the true horror of Derry, Maine, is not the clown in the sewer, but the apathy of the town above it. The adults are either perpetrators of abuse or willfully blind to it, creating a vacuum of safety that allows the entity, Pennywise, to thrive. The monster is less an invader and more a symptom of a town that has forgotten how to love its children.

Visually, the film is a masterclass in contrast, spearheaded by cinematographer Chung-hoon Chung (known for his work with Park Chan-wook). The lens captures the summer of 1989 in a haze of golden, nostalgic warmth—sun-drenched quarries and bicycle rides—which makes the sudden plunges into darkness all the more violating. The aesthetic beauty of the "Losers Club" bonding scenes serves as a cruel counterpoint to the subterranean grimness they must eventually face.

The production design of the Neibolt Street house, a rotting architectural sore in the middle of the town, acts as a physical manifestation of the children's collective psyche: broken, abandoned, and filled with dark corners where repressed fears fester. Muschietti uses the camera to shrink the children, often framing them against looming structures or vast, empty spaces, emphasizing their isolation in a world that feels too big and too dangerous to navigate alone.

However, the film’s heartbeat resides entirely in its cast. The "Losers Club" is not a collection of tropes but a genuine ensemble of wounded souls. Jaeden Martell’s Bill is driven by a grief so palpable it feels heavy on the screen, while Sophia Lillis, as Beverly, delivers a performance of heartbreaking maturity, battling a domestic horror that is far more terrifying than any supernatural clown.

Then there is Bill Skarsgård. His Pennywise is a performance of glitching, feral intensity. Unlike Curry’s gravelly, human-like gangster in greasepaint, Skarsgård plays the entity as something barely containing its own hunger. He drools, his eyes drift apart, and his voice cracks like a prepubescent boy’s before dropping into a guttural growl. He is an unpredictable, rabid animal trying to wear a human suit, and the fit is all wrong. This alien quality makes the predator-prey dynamic disturbingly visceral.

Ultimately, *It* succeeds because it respects the gravity of childhood fear. It acknowledges that for a child, the world is naturally terrifying—filled with bullies, abusive parents, and the looming specter of mortality. By externalizing these anxieties into a dancing clown, the film allows its young heroes to do what they cannot do in real life: punch the monster in the face. It is a cathartic, visually arresting piece of cinema that asserts, quite powerfully, that while we cannot stop the darkness from coming, we do not have to face it alone.