The Sterile Pulse of the AfterlifeCinema has a long, troubled relationship with necromancy—both in its narratives and in its business model. There is an irony in remaking *Flatliners* (1990), a film explicitly about the dangers of disturbing the natural order of death. Niels Arden Oplev’s 2017 update, which technically postures as a sequel through a grimly ironic Kiefer Sutherland cameo, serves as an unintentional meta-commentary on the reboot culture itself: just because you have the technology to bring something back to life doesn't mean it will return with a soul.

The Lens

The LensWhere Joel Schumacher’s original film was a sweaty, operatic fever dream of steam tunnels, gothic statuary, and neon-drenched purgatory, Oplev’s interpretation is clinically, suffocatingly clean. The director, known for the grit of the original *The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo*, here trades atmosphere for the aesthetic of a high-end pharmaceutical commercial. The basement lab, once a forbidden dungeon of rogue science, now looks like an Apple Store after hours—all brushed steel, glass, and bright, flat lighting.

This visual shift is disastrous for the film’s tension. The horror of the afterlife should feel intrusive and ancient, a violation of the sterile medical world. Instead, the digital hallucinations that haunt the characters—glitching faces and generic CGI decay—feel perfectly at home in this plastic environment. There is no texture to the terror. When the characters cross over, they don't descend into a Dantesque underworld; they merely enter a screensaver of their own trauma.

The Heart

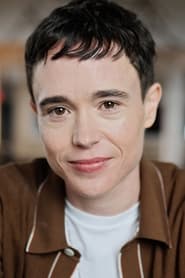

The HeartThe narrative spine of *Flatliners* is the concept of atonement. The medical students, led by the intense and burdened Courtney (Elliot Page), seek to map the brain during death, but they inadvertently unlock a Pandora’s box of their own sins. The premise is fertile ground for psychological drama: what if our guilt is the only thing waiting for us on the other side?

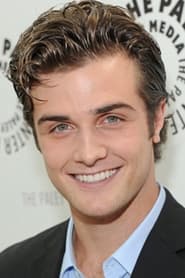

However, the film collapses under a fundamental misunderstanding of human frailty. The "sins" that haunt these characters range from the horrific to the mundane, yet the film treats them with the same generic jump-scare mechanics. Elliot Page brings a necessary gravity to Courtney, playing the role with a brittle desperation that suggests a much better, deeper movie was left on the cutting room floor. Diego Luna, usually a charismatic presence, is trapped in the thankless role of the moral scold.

The most jarring tonal shift occurs in the first act, where the near-death experience functions essentially as a "smart drug." The characters return from death not shaken by the void, but energized, partying, and suddenly brilliant at their jobs. It reduces the profound mystery of mortality to a bio-hack for yuppie overachievers, stripping the narrative of its philosophical weight before the horror elements even arrive.

The Verdict

The Verdict*Flatliners* (2017) is a cautionary tale, though perhaps not the one the filmmakers intended. It demonstrates that sleek production values and a talented cast cannot mask a hollow script. By trying to rationalize the supernatural with scientific jargon and resolve complex trauma with simple plot mechanics, the film creates a heartbeat that registers on the monitor, but never truly quickens. It is a resurrection that should have been left undisturbed.