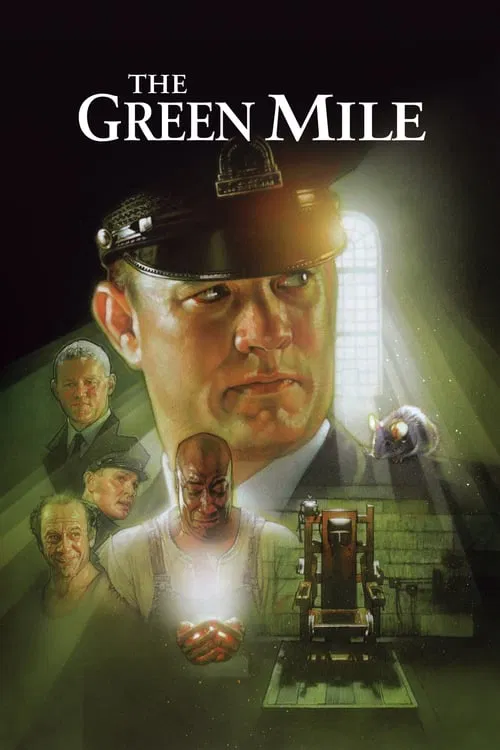

The Weight of SilenceIn the canon of American cinema, 1999 was a year of noise—the kinetic nihilism of *Fight Club*, the digital revolution of *The Matrix*, the suburban scream of *American Beauty*. Yet, amidst this cacophony, Frank Darabont released a film that spoke in a whisper, a three-hour "sad prayer" about the fragility of goodness in a brutal world. *The Green Mile*, Darabont’s second pilgrimage into the prison writings of Stephen King, is often reductively compared to its sibling, *The Shawshank Redemption*. But where *Shawshank* is a hymn to the indomitable human spirit, *The Green Mile* is a eulogy for it. It is a film not about how we survive, but about what we kill to maintain our order.

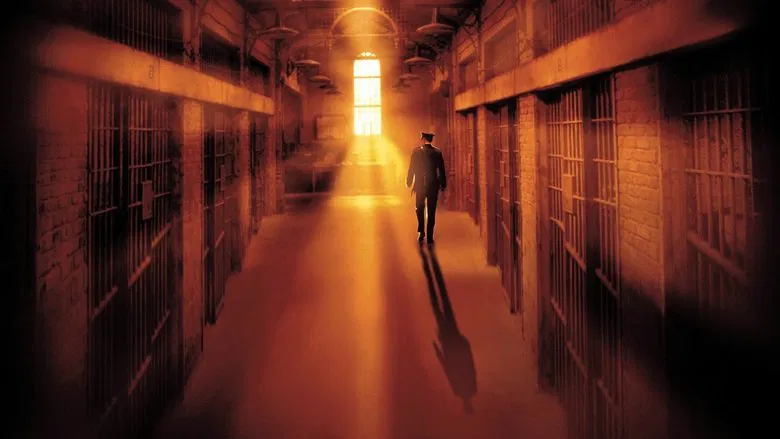

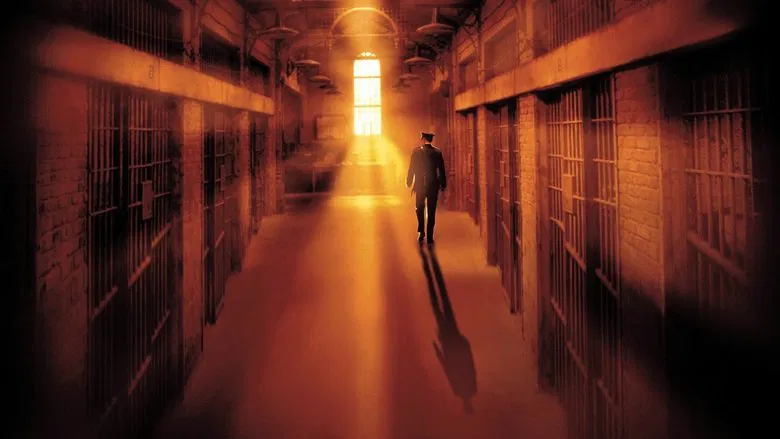

Darabont’s visual language here is heavy, almost suffocatingly terrestrial. The Cold Mountain Penitentiary is not filmed as a place of rehabilitation but as a purgatory waiting room. The cinematographer, David Tattersall, bathes the "Green Mile"—the lime-colored linoleum floor leading to the electric chair—in a sickly, institutional glow that contrasts with the golden, ethereal light surrounding John Coffey. The prison set is cramped, forcing the characters into tight frames that heighten the intimacy of their interactions. We are not observing these men from a distance; we are locked in the cage with them, smelling the stale air and the impending ozone of the chair.

The film’s narrative architecture rests on a fantastical premise: John Coffey (Michael Clarke Duncan), a hulking Black man on death row in 1930s Louisiana, possesses the miraculous power to heal. However, to view this purely as a supernatural mystery is to miss the tragic racial subtext that complicates the film’s legacy.

We must address the specter in the room: John Coffey is frequently cited as a textbook example of the "Magical Negro" trope—a character of color with mystical abilities whose sole narrative function is to aid the white protagonist. There is validity to this critique. Coffey has no past, no family, and no desires other than to absorb the pain of others. Yet, Duncan’s performance transcends the limitations of the script. He plays Coffey not as a plot device, but as a creature of pure, agonizing empathy. His refrain, "I'm tired, boss," is not just a resignation to death, but a crushing indictment of a world that is too cruel for a being of such gentleness.

The film’s true horror lies not in the supernatural, but in the mundane bureaucracy of death. The antagonists are not monsters, but systems. Even the villainous guard Percy Wetmore (Doug Hutchison) is terrifying not because he is powerful, but because he is petty, protected by nepotism and emboldened by the badge.

The contrast between the "monsters" is stark: Coffey, the condemned child-killer who is actually a saint, versus "Wild Bill" Wharton (Sam Rockwell), a chaotic force of malice who represents the arbitrary nature of evil. But the moral center is Tom Hanks’ Paul Edgecomb. Hanks delivers a performance of quiet devastation. He is the Pontius Pilate of this story—a decent man washing his hands of a sin he knows he is committing, trapped by the very laws he swore to uphold. The tragedy is not that he fails to save Coffey, but that he understands exactly what he is destroying.

Ultimately, *The Green Mile* is an endurance test of the heart. It demands we sit in the dark and witness the execution of innocence. It does not offer the cathartic escape of *Shawshank’s* Zihuatanejo beach; instead, it leaves us with a lingering, uncomfortable question about the cost of justice. It suggests that miracles do exist, but we—through fear, prejudice, or simple bureaucratic inertia—are compelled to extinguish them. In a modern era obsessed with anti-heroes and moral ambiguity, Darabont’s masterpiece remains a piercing reminder that sometimes, the greatest evil is simply doing your job.