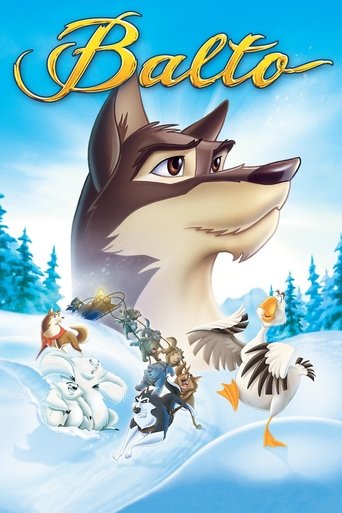

The Heart Beneath the IceHistory has a habit of remembering the finish line while forgetting the marathon. For nearly a century, popular culture has canonized Balto, the sled dog who trotted the final fifty miles of the 1925 Alaskan serum run, as the savior of Nome. Ericson Core’s *Togo* does not merely offer a correction to this record; it offers a rebuke to the very idea that heroism is defined by public glory. This is not a film about a accolades, but about the brutal, silent work of survival. It is a Disney film in name, but in spirit, it is a survivalist western set against the indifference of the frozen North.

Director Ericson Core, serving as his own cinematographer, rejects the glossy, saturated aesthetic often associated with the genre. Instead, he paints the Alaskan tundra in bruises of blue, grey, and blinding white. The visual language here is muscular and imposing. When the sled team traverses the Norton Sound—a cracking, heaving sheet of ice that threatens to swallow them whole—the camera does not treat it as a theme park ride, but as a suffocating reality. The CGI, while present, is anchored by a tangible sense of cold; you can almost hear the wood of the sled groaning under the strain of the gale. Core understands that the landscape is not just a backdrop, but the antagonist itself, a leviathan that Leonhard Seppala (Willem Dafoe) must negotiate with rather than conquer.

At the center of this storm is Willem Dafoe, an actor whose face is as weathered and expressive as the terrain he traverses. Casting Dafoe was a masterstroke; he brings a Shakespearean gravitas to a role that could easily have dissolved into sentimental mush. His Seppala is not a man who coos at puppies. He is a pragmatist who views his dogs as engines of survival. The film’s emotional intelligence lies in the slow erosion of this stoicism. The narrative structure, which intercuts the death-defying serum run with flashbacks of Togo as an "unmanageable" puppy, serves to deconstruct Seppala’s own walls. We watch him learn that Togo’s defiance—the very trait he tried to breed out of the animal—is actually an indomitable will that mirrors his own.

The film’s most profound moments are often its quietest. There is a specific sequence where Seppala, realizing the impossibility of the task ahead, recites a variation of the St. Crispin’s Day speech to his dogs. In the hands of a lesser actor, it would be laughable; in Dafoe’s, it is a prayer to the only creatures on earth who understand his existence. The chemistry between Dafoe and the lead dog (played by a descendant of the real Togo named Diesel) transcends the "boy and his dog" trope. It evolves into a portrait of mutual respect between two veterans who have left everything on the ice.

Ultimately, *Togo* succeeds because it refuses to sanitize the cost of heroism. The journey leaves scars, both physical and emotional. By the time the credits roll, the film has earned its tears not through manipulation, but through the sheer exhaustion of the journey. It is a sturdy, beautiful piece of filmmaking that reminds us that the most important stories are often the ones that history—and Hollywood—forgot to tell.