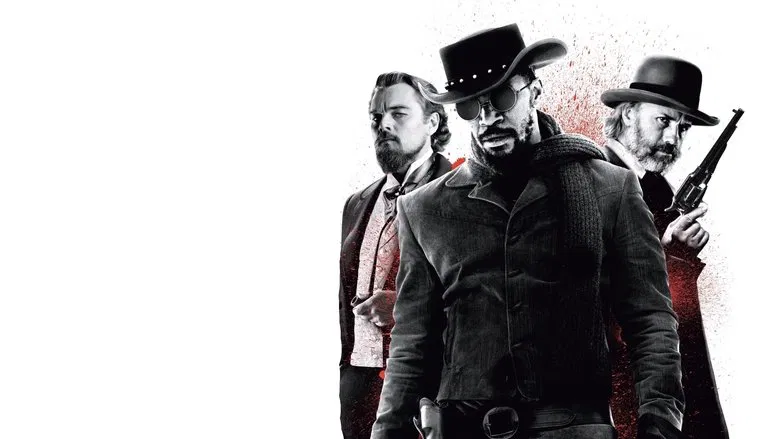

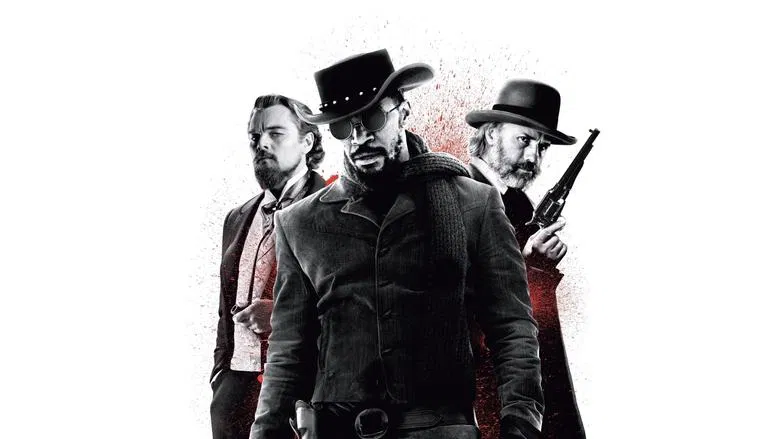

The Opera of Blood and ChainsIf history is a nightmare from which we are trying to awake, Quentin Tarantino prefers to lucid dream. With *Django Unchained* (2012), the director continues the project he began in *Inglourious Basterds*: the weaponization of cinema to rewrite the sins of the past. Yet, unlike his Nazi-scalping fantasy, *Django* ventures into the open wound of American slavery, applying the garish, pop-art aesthetics of a Spaghetti Western to a subject usually reserved for somber, Oscar-baiting dramas. The result is a film that is purposefully jagged—simultaneously a roaring rampage of revenge and a deeply uncomfortable interrogation of how we consume violence.

Visually, Tarantino abandons the claustrophobia of the plantation for the grand, mythic scope of the American West (and South). Collaborating with cinematographer Robert Richardson, he paints the antebellum South not as a dusty historical reenactment, but as a vibrant, terrifying opera. The camera loves the sudden burst of red blood on white cotton; it lingers on the opulent, velvety interiors of the "Big House" just as lovingly as it does on the scarred back of Django (Jamie Foxx). This dissonance is the point. By framing the atrocities of slavery through the lens of Sergio Corbucci-style exploitation cinema, Tarantino forces the audience to confront the absurdity of the institution itself. The violence is stylized, yes, but the cruelty—dogs tearing a man apart, men fighting to the death for sport—is depicted with a sickening thud that strips away the "cool" factor usually associated with the director's work.

At the narrative’s dark heart sits the dinner table sequence at Candieland, a masterclass in tension that rivals the tavern scene in *Inglourious Basterds*. Here, the film sheds its gun-slinging bravado for psychological horror. Leonardo DiCaprio’s Calvin Candie is a villain of terrifying joviality, a man who treats human suffering as parlor entertainment. The moment DiCaprio slams his hand onto the table—accidently shattering a glass and slicing his palm for real—anchors the film’s erratic tone in visceral reality. He doesn't break character; he smears his actual blood over the face of Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), turning a scripted moment into a grotesque improvisation of ownership. It is a scene that encapsulates the film's thesis: the Southern aristocracy was not merely complicit in evil, but theatrically devoted to it.

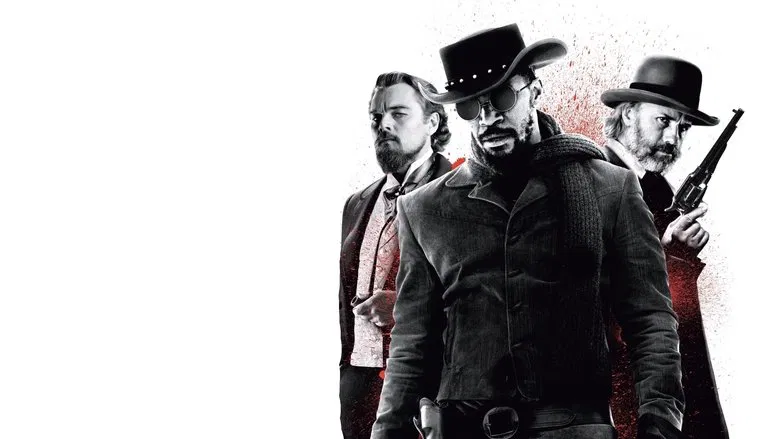

However, the film’s triumph rests on the shoulders of Jamie Foxx. In a movie populated by chatterboxes—Christoph Waltz’s verbose Dr. Schultz and Samuel L. Jackson’s chillingly complicit Stephen—Foxx delivers a performance of silent, simmering physicalit. His Django is not a superhero from frame one; we watch him learn to unclench his jaw, to straighten his spine, and eventually, to adopt the swagger of the folk hero he is destined to become. His silence is the loudest thing in the movie, a vacuum that sucks in the racist rhetoric around him and spits it back out as righteous fire.

*Django Unchained* is not a history lesson, and it was never meant to be. It is a cinematic exorcism. It argues that sometimes, the only way to process the sheer scale of historical trauma is to burn the house down. While its oscillation between slapstick humor and profound brutality can be jarring, that friction is where the film finds its truth. It refuses to be polite about an impolite history, leaving us exhilarated, exhausted, and morally queasy—exactly as we should be.