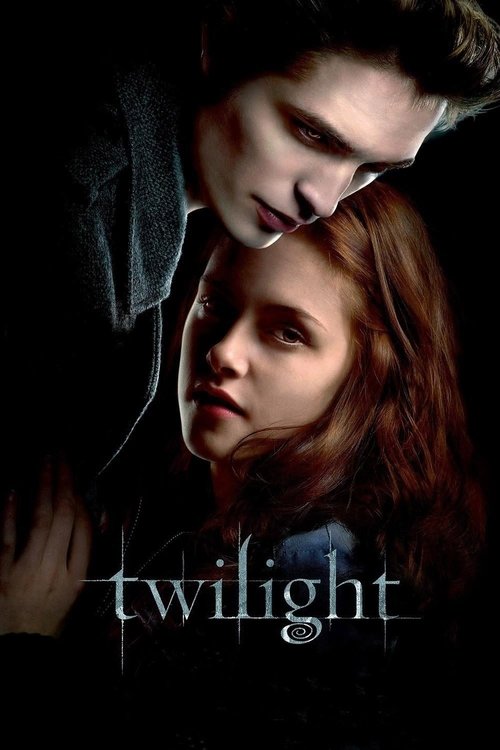

The Blue Hour of AdolescenceTo discuss Catherine Hardwicke’s *Twilight* (2008) in the present day is to wade through a decade of irony, memes, and retrospect. For years, the film was the easy punchline of cinema—derided for its melodrama, its sparkling vampires, and its lip-biting awkwardness. Yet, to dismiss it as merely a commercial product for screaming teenagers is to overlook the distinct, feverish artistry at its core. Unlike the polished, studio-safe sequels that followed, Hardwicke’s original film is a piece of genuine indie filmmaking, a raw, hormonal mood piece that captures the terrifying intensity of first love better than perhaps any fantasy film of its era.

Hardwicke, who previously directed the harrowing teen drama *Thirteen*, approaches the supernatural romance of Bella Swan and Edward Cullen not as an epic, but as a sensory experience of anxiety and desire. The film is suffocated by a specific visual language: the now-infamous "blue tint." This was not a mistake, but a choice. The Pacific Northwest of Hardwicke’s vision is perpetually damp, cold, and bruised. The color grading strips the warmth from the world, isolating Bella and Edward in a glaucous dreamscape where time seems suspended.

This aesthetic choice transforms the film from a standard adaptation into a visual translation of teenage angst. The camera is rarely still; it is handheld, shaky, and intimate, mimicking the restless energy of adolescence. When Bella walks through the high school cafeteria or navigates the wet parking lot, the lens feels invasive, mirroring her own self-consciousness. The film understands that to a seventeen-year-old, the difference between a crush and a predator, or a soulmate and a monster, is thrillingly thin. The supernatural elements are almost secondary to the overwhelming, crushing weight of simply *wanting* someone this much.

Nowhere is the film’s unique energy more palpable than in the celebrated baseball sequence. Set to Muse’s "Supermassive Black Hole," the scene is a explosion of camp and kinetic joy. It is one of the few moments where the vampires are allowed to be physical without being predatory, playing their sport under the cover of thunder. It is stylish, bizarre, and utterly sincere—a perfect encapsulation of Hardwicke’s ability to merge the gothic with the modern.

Ultimately, *Twilight* endures not because of its vampire lore, but because of its emotional fidelity. Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson perform with a stammering, intense chemistry that feels less like a script and more like two people drowning in pheromones. The film doesn't apologize for the irrationality of teenage love; it elevates it to myth. While later installments would smooth out the rough edges and brighten the color palette, losing the soul in the process, the 2008 original remains a singular artifact: a strange, beautiful, blue-drenched fever dream that validates the catastrophic feelings of youth.