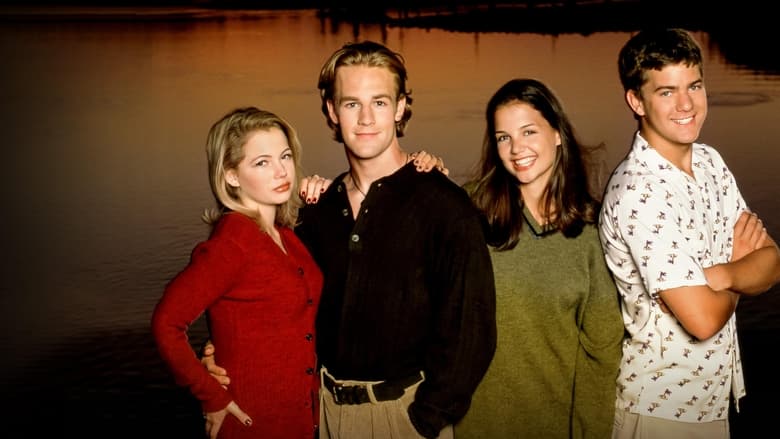

The Verbal HorizonTo revisit *Dawson’s Creek* nearly three decades after its premiere is to step into a peculiar artifact of late-90s ambition—a time when television began to demand the same emotional literacy as the independent cinema of its era. Created by Kevin Williamson, freshly minted from the deconstructionist success of *Scream*, the series was never merely a soap opera about raging hormones. It was a verbal experiment. It posited a world where teenagers possessed the vocabulary of 40-year-old psychoanalysts, a creative choice that was initially mocked but ultimately revealed the show’s true thesis: that the feelings of youth are so large, so cataclysmic, that they require a heightened language to contain them.

Visually, the series established a distinct texture that separated it from the glossy, polished corridors of its successor, *The O.C.*. The fictional Capeside is filmed with a golden, hazy nostalgia—a Spielbergian "magic hour" that seems to stretch on forever. The director of the pilot, Steve Miner, utilized the physical geography of the creek not just as a setting, but as a boundary line between childhood innocence and the encroaching adult world. The water is calm, yet it separates the homes of Dawson Leery (James Van Der Beek) and Joey Potter (Katie Holmes), necessitating a rowboat or a ladder climb to bridge the gap. This physical traversing of space becomes the show's central metaphor: the exhausting, terrifying effort required to reach another person.

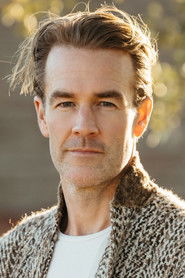

The heart of the narrative, however, lies in its subversion of the "soulmate" mythos. The series begins by selling us the inevitability of Dawson and Joey—the filmmaker and the muse, the neighbors destined for romance. But as the seasons progress, the show performs a fascinating autopsy on this trope. Dawson, with his rigid adherence to cinematic idealism, represents the way we *want* love to look: scripted, directed, and perfect. In contrast, Pacey Witter (Joshua Jackson) emerges as the agent of chaotic, messy reality. The friction between these two modes of loving—the projected ideal versus the lived experience—elevates the series above its genre trappings. It asks a profound question: Is a soulmate a mirror that reflects who you were, or a force that challenges who you are becoming?

We must also acknowledge the tragedy of Jen Lindley (Michelle Williams), the "interloper" who was frequently punished by the narrative for her perceived sins of experience. Williams, even then, displayed a raw, vibrating vulnerability that hinted at the powerhouse actress she would become. Her character’s arc is the show’s most bruised fruit, a reminder that in this idyllic town of verbose introspection, some wounds cannot be talked away. The series finale, often cited as one of the most satisfying in television history, honors this by refusing to grant everyone a fairy tale, instead opting for a poignant mix of grief and forward momentum.

Ultimately, *Dawson’s Creek* remains a vital text not because of its plot mechanics, but because it took the inner lives of young people seriously. It refused to talk down to its audience, insisting that a heartbreak at sixteen is as valid and devastating as a divorce at forty. It captured the specific agony of growing up—the realization that the script you wrote for your life is being rewritten by everyone around you, in real-time, without your permission.