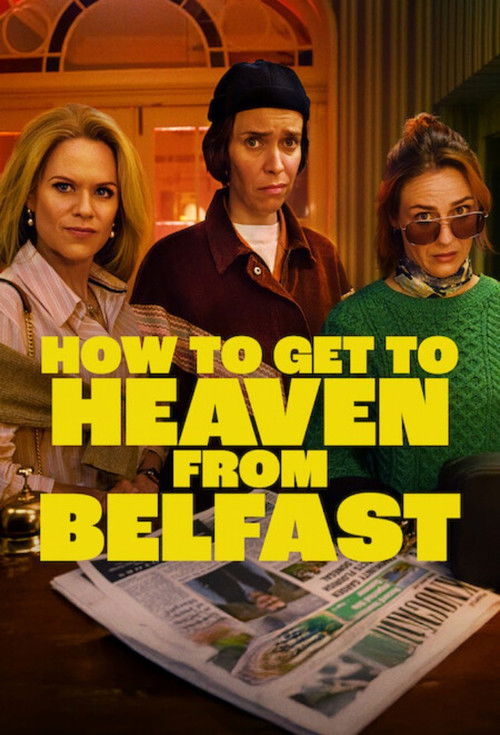

The Weight of SilenceThere is a specific, suffocating texture to the silence that hangs between old friends who know too much about one another. In *How to Get to Heaven from Belfast*, creator Lisa McGee trades the frantic, uniform-clad exuberance of *Derry Girls* for something darker, knottier, and altogether more perilous. While the marketing machine might label this a comedy-thriller, McGee has quietly crafted a meditation on the erosion of memory and the way trauma, when left to ferment in the damp air of Northern Ireland, eventually turns volatile. It is not merely a "whodunnit"; it is a "who-have-we-become."

McGee’s visual language here is a stark departure from the sitcom brightness of her previous work. Director Michael Lennox bathes the series in a slate-grey palette, capturing the rugged, unforgiving beauty of the Irish coast not as a travel brochure, but as a trap. The camera lingers on the negative space between the three leads—Saoirse (Roisin Gallagher), Robyn (Sinéad Keenan), and Dara (Caoilfhionn Dunne)—emphasizing the ghostly presence of the fourth, estranged friend whose death sets the narrative in motion. The sound design is equally oppressive; the wind is a constant, howling character, often drowning out the dialogue, forcing the audience to lean in, to strain for the truth just as the characters do.

At the heart of the series is a ferocious deconstruction of female friendship in middle age. This is not the sanitized, wine-mom solidarity often peddled by lesser dramas. Saoirse, Robyn, and Dara are bound less by affection and more by the gravity of a shared, unspeakable past. Roisin Gallagher is particularly devastating as Saoirse, a successful TV writer whose professional competence masks a profound internal disintegration. Watching her navigate the wake of their friend Greta, we see the cracks in the veneer—the manic deflection, the biting wit used as a shield. The scene where the trio returns to the site of their childhood trauma—a burnt-out structure in the woods—is a masterclass in tension. It captures the terrifying realization that the people who know you best are also the ones most capable of destroying you.

Ultimately, *How to Get to Heaven from Belfast* succeeds because it refuses to let its mystery overtake its humanity. The "caper" elements—the missing evidence, the shadowy figures—are merely the scaffolding for a story about the impossibility of outrunning one's history. McGee suggests that in a place like Belfast, where the past is physically inscribed on the landscape, "heaven" isn't a destination or a reward. It is simply the moment you stop running, turn around, and finally look the ghost in the eye. This is a brave, messy, and essential piece of television that cements McGee as one of the most vital voices in modern drama.