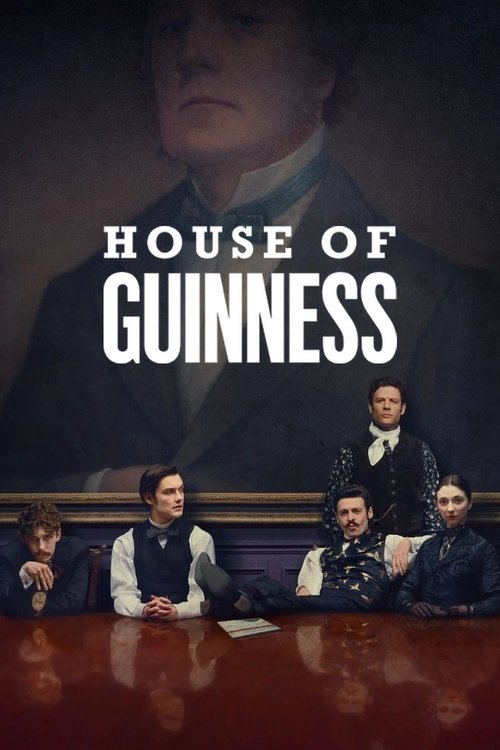

The Bitter Draught of AmbitionThere is a distinct, unmistakable texture to a Steven Knight production—a specific alchemy of soot, slow-motion swagger, and anachronistic electric guitars that screams modernity while wearing the costumes of the past. In *House of Guinness*, Knight attempts to pour this signature formula into a new vessel: the 19th-century brewing dynasty that gave the world its most famous stout. The result is a series that, much like the drink itself, takes time to settle, offering a rich, dark aesthetic that occasionally hides a lack of substantial body.

The premise is pure dynastic melodrama, inviting inevitable comparisons to *Succession* by way of Dickens. We are dropped into Dublin, 1868. The patriarch, Sir Benjamin Guinness, has died, leaving behind a power vacuum, a massive fortune, and four children ill-equipped to handle either. The narrative engine is sparked by the reading of the will, a scene played with delicious, suffocating tension. It cleaves the family in two: the "lords of the vat," Arthur (Anthony Boyle) and Edward (Louis Partridge), are handed the keys to the kingdom, while their siblings Anne (Emily Fairn) and Benjamin (Fionn O'Shea) are left to drift in the margins of aristocracy.

Visually, the series is a triumph of mood over geography. Filmed largely in the industrial corridors of Northern England rather than the modern streets of Dublin, the show constructs a fantasy version of the Irish capital. It is a city of smoke and shadow, where the brewery looms like a steampunk fortress, a mechanical beast demanding to be fed. Cinematographers Nicolai Brüel and Joe Saade shoot the fermentation vats with a reverence usually reserved for religious icons, emphasizing the sheer, overwhelming scale of the industry. However, this stylized approach comes at a cost. The Dublin on screen feels less like a living, breathing city and more like a stage set for Knight’s trademark rock-and-roll history. The complex political powder keg of the Fenian uprising is often reduced to background noise—a texture of unrest rather than a deeply explored reality.

The emotional weight of the series rests heavily on Anthony Boyle’s Arthur. Boyle imbues the eldest son with a frantic, tragic energy; he is a man suffocating under the weight of expectation and a secret personal life that 1868 society would destroy him for. His performance anchors the show, finding the human pulse beneath the high collars and top hats. Yet, the show struggles to decide if it wants to be a serious examination of Anglo-Irish class dynamics or a pulpy thriller. The introduction of James Norton’s Sean Rafferty—a fictional enforcer who serves as the "Tommy Shelby" of the piece—tips the scales toward the latter. While Norton is magnetic, his subplot involving explosions and underworld dealings sometimes feels like it belongs in a different show, distracting from the more compelling domestic warfare occurring within the drawing rooms of the Guinness estate.

Ultimately, *House of Guinness* is a compelling, if imperfect, study of legacy. It asks whether the institutions we build are destined to crush the individuals who inherit them. While it may infuriate historians and those looking for a nuanced depiction of Irish identity—the "feral" depiction of the lower classes is a particularly jagged pill to swallow—it succeeds as a piece of operatic storytelling. It is a show about the suffocating nature of privilege, brewed with style, even if the aftertaste is slightly more bitter than intended.