The Architecture of VengeanceIn the sprawling landscape of Chinese period dramas, where court intrigues often dissolve into soapy melodrama, Pan Anzi’s *The Vendetta of An* (2025) arrives like a blade of ice—sharp, transparent, and chillingly precise. It is a series that initially masquerades as a standard revenge procedural but quickly reveals itself to be a meditation on the cost of obsession. Pan, whose previous work like *Under the Microscope* demonstrated a flair for kinetic, detail-oriented storytelling, here trades the frenetic for the forensic. He constructs a version of Chang’an that is not merely a historical backdrop, but a suffocating labyrinth where every smile conceals a dagger and every silence screams.

Visually, the film operates in a register of claustrophobic grandeur. Unlike the golden-hued warmth typical of the genre, Pan and his cinematographer drape the capital in slate greys, bruised purples, and the relentless white of winter snow. The camera often lingers on the negative space around Xie Huai’an (played with terrifying restraint by Cheng Yi), emphasizing his isolation even in crowded courtrooms. This is a visual language that mirrors the protagonist’s internal state: a man who has hollowed himself out to become a vessel for retribution. The "Twenty-Four Strategies" of the alternate title are not just plot points; they are the architectural blueprints of a prison Xie Huai’an has built for himself, and Pan shoots them with the clinical detachment of a dissection.

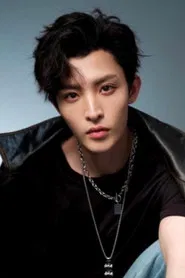

At the center of this frozen world is Cheng Yi’s performance, which defies the industry’s current obsession with explosive, "clip-able" acting. As Xie Huai’an, the survivor of a military purge returning under the guise of a lowly registrar, Cheng works in micro-expressions. He is a ghost haunting the living, his eyes deadened by a decade of plotting yet flickering with a terrifying intelligence. The "conversation" surrounding the film has rightly focused on the "snow scene"—a moment of grief so raw it went viral—but the true marvel is his stillness. In scenes opposite veteran heavyweights like Liu Yijun (as the usurper Emperor Xiao Wuyang) and Wang Jinsong, Cheng holds his own not by raising his voice, but by lowering the temperature in the room.

The narrative, however, is not without its stumbling blocks. In its ambition to weave a complex web of "schemes within schemes," the series occasionally collapses under its own intellectual weight. The plot, which sees Xie Huai’an manipulating the political landscape to avenge the Huben Army, demands a level of suspension of disbelief that borders on the fantastical. There are moments where the antagonists—supposedly brilliant tacticians—walk into traps that feel too perfectly laid, stripping the conflict of some tension. Furthermore, the relentless bleakness can be exhausting; the show rarely allows its audience, or its characters, to breathe, creating a relentless forward momentum that sometimes sacrifices emotional resonance for plot mechanics.

Yet, *The Vendetta of An* succeeds because it refuses to frame revenge as a heroic act. By the time the final gambits are played, the "victory" feels indistinguishable from defeat. Pan Anzi asks us to consider what remains of a man when his life’s purpose is destruction. It is a grim, stylish, and often profound piece of television that elevates the genre by treating the thirst for vengeance not as a fire that purifies, but as a cold that preserves the dead while killing the living. In a year of loud blockbusters, this quiet, lethal drama offers the most deafening silence of all.