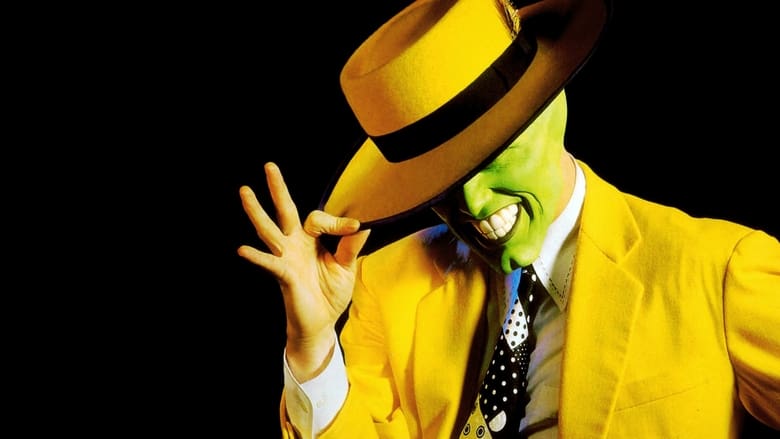

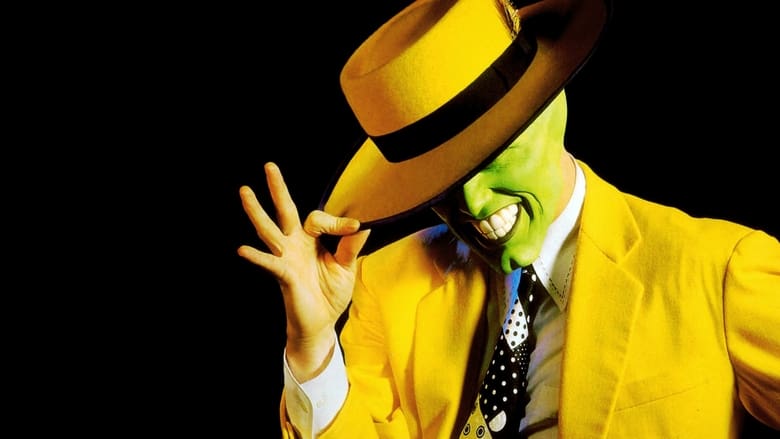

The Chaos of the Repressed SelfIf 1994 was the year Jim Carrey ascended from comedian to cultural deity—releasing *Ace Ventura*, *Dumb and Dumber*, and *The Mask* in a single calendar run—then *The Mask* is arguably the most psychologically revealing of the triumvirate. While the other films relied on stupidity as a virtue, director Chuck Russell’s adaptation of the Dark Horse comic serves as a kinetic study of the Id. It is a film about the terrifying, exhilarating freedom of abandoning social contracts. We often remember the yellow zoot suit and the catchphrases, but we forget that this is fundamentally a story about a man who needs to become a monster to survive his own mediocrity.

Visually, Russell—whose background lies in the visceral horror of *A Nightmare on Elm Street 3* and *The Blob*—constructs "Edge City" as a sweaty, neon-noir fever dream. It feels like a Gotham City that has stopped taking its medication. The director understands that for the comedy to land, the world around it must feel oppressive. The police station, the damp garage, and the claustrophobic bank are designed to crush the spirit of Stanley Ipkiss (Carrey).

When the transformation occurs, it isn't merely a costume change; it is a violent expulsion of energy. The visual effects by Industrial Light & Magic were revolutionary not just for their technical polish, but for their conceptual audacity. They brought the anarchic physics of Tex Avery cartoons into a live-action space, blurring the line between flesh and ink. When the Mask’s eyes bulge or his jaw hits the table, it is grotesque, bordering on body horror, yet played for laughs—a perfect visual metaphor for the internal pressure cooking inside a repressed man.

At its heart, however, *The Mask* is a tragedy that learns to laugh. Stanley Ipkiss is not just a "nice guy"; he is a doormat, a man so paralyzed by the Superego—the rules of society, the fear of offending—that he has ceased to really live. The brilliance of the narrative lies in the nature of the artifact itself. Unlike traditional superhero cowls that hide an identity to protect the innocent, this mask reveals the wearer's true self. The green-faced trickster isn't a separate entity; he is Stanley without brakes. He is pure, unadulterated desire.

This dynamic elevates the romance with Tina Carlyle (Cameron Diaz, in a star-making debut that feels crafted from celluloid dreams). The relationship subverts the classic noir trope where the femme fatale destroys the hero. Here, she falls for the monster, but the film’s emotional climax argues that the monster’s confidence acts as a bridge. Stanley doesn't need to *be* the Mask forever; he just needs to remember that the Mask’s bravery comes from his own psyche.

Ultimately, *The Mask* endures not because of its special effects, which have naturally aged, but because of its manic honesty. It taps into the universal, darker fantasy of consequences-free living. In the "Cuban Pete" musical number—a scene that holds the police force hostage with the sheer power of rhythm—we see the film’s thesis: joy is a weapon, and chaos is the only antidote to a rigid world. Russell and Carrey delivered a comic book movie that feels less like a hero's journey and more like a therapy session conducted at 100 miles per hour.