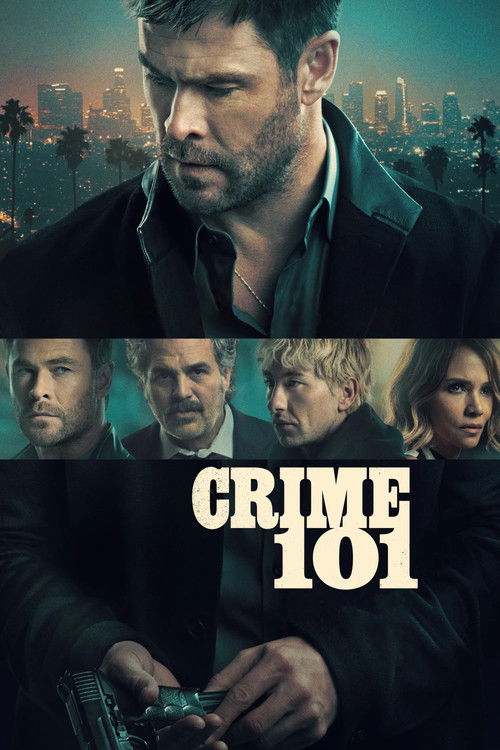

The Art of the Clean GetawayIn the vocabulary of the modern blockbuster, "restraint" is usually a dirty word. We live in an era of maximalist cinema, where stakes must be apocalyptic and the volume perpetually cranked to eleven. This is why Bart Layton’s *Crime 101* feels less like a typical 2026 release and more like a mesmerizing artifact from a lost timeline—a sun-bleached, asphalt-noir that values process over pyrotechnics. Layton, who dismantled the heist genre with the docu-narrative hybrid *American Animals* (2018), has returned not to deconstruct the form, but to perfect it. Adapting Don Winslow’s novella, he delivers a film that operates much like its protagonist: efficient, meticulous, and obsessed with the friction between a code of conduct and the chaos of human desire.

Layton’s visual language here is a study in "California lonely." Gone is the frenetic, unreliable editing of his previous work. In its place is a patient, widescreen gaze that captures the hypnotic monotony of the Pacific Coast Highway. The cinematography treats the 101 freeway not just as a setting, but as a circulatory system for the film’s moral ambiguity. The heat radiates off the tarmac; the ocean glares with an indifferent beauty. Layton understands that the most tension isn't found in a gunfight, but in the silence of a car interior where a man is deciding whether to turn the wheel left or right. The film’s sound design mirrors this, favoring the hum of tires and the rhythmic breaking of waves over an intrusive score, allowing the ambient noise of Los Angeles to suffocate the characters.

At the center of this silence is Chris Hemsworth, shedding the weight of comic book mythology to play the thief—a man defined entirely by his discipline. It is a performance of subtraction. Hemsworth plays the character as a void wrapped in charisma, a man who has hollowed himself out to fit perfectly inside his own rules. He is the "Crime 101" of the title: a living manual of survival that forbids attachment.

However, the film’s emotional pulse beats most surprisingly through Mark Ruffalo’s Detective Lubesnick and Halle Berry’s insurance broker. Ruffalo, often cast as the rumpled conscience, here plays a man whose obsession is quiet, almost sad. He isn’t chasing a criminal so much as he is chasing a ghost that proves his own competence. The "cat and mouse" dynamic is standard genre fare, but Layton frames it as two lonely professionals acknowledging each other across a void. The pivotal scene in the diner—a genre staple since *Heat*—is subverted here. It’s not a clash of titans, but a weary recognition of shared entrapment. They are both men who have sacrificed their lives to their respective "crafts," leaving them with nothing but the chase.

If the film stumbles, it is perhaps in its refusal to accelerate. Audiences trained on the dopamine hits of rapid-fire editing may find the middle act languid. Yet, this pacing is deliberate. Layton forces us to sit in the discomfort of the wait, to feel the boredom that necessitates the adrenaline of the score. The introduction of Barry Keoghan as a volatile variable injects a necessary dose of anarchy, threatening to burn down the carefully constructed house of cards Hemsworth’s character has built.

*Crime 101* ultimately asks whether it is possible to live without leaving a trace. In a world of digital surveillance and oversharing, the thief’s analog anonymity feels like a superpower. But Layton’s lens reveals the tragedy inherent in that power: to be untraceable is to be alone. The film concludes not with a bang, but with a lingering shot of the coastline—beautiful, empty, and moving constantly forward, indifferent to the crimes committed on its edge. It is a stylish, adult thriller that respects the intelligence of its audience, reminding us that the most dangerous traps are the ones we set for ourselves.