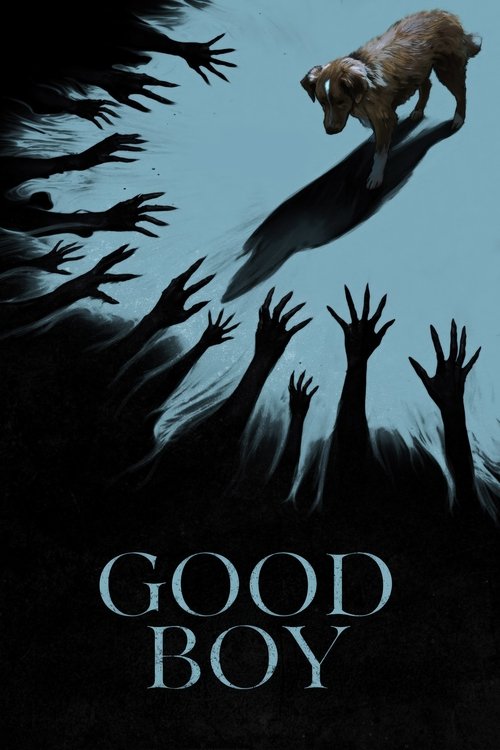

The Silent WitnessIn the vast, noisy landscape of modern horror, where jump scares are often quantified by decibels and body counts, Ben Leonberg’s *Good Boy* (2025) arrives as a quiet, devastating anomaly. It is a film that dares to ask a question both simple and profound: What does our suffering look like to those who love us most, but cannot understand a word we say? By anchoring its camera—and its soul—strictly to the eye level of a Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever named Indy, Leonberg transforms a micro-budget haunted house story into a crushing elegy for terminal illness. This is not merely a creature feature; it is a study of helplessness, viewed through eyes that offer only unconditional love.

Leonberg’s visual language is the film’s most striking gamble. There are no sweeping drone shots or convenient omniscient angles. The camera lives at knee-height, navigating the geography of a rural farmhouse with a canine’s sensory focus. We see the world in fragments: the scuff of a boot, the underside of a table, the looming, incomprehensible faces of weeping adults. This constraint creates a suffocating intimacy. When the supernatural elements begin to encroach—manifesting as muddy, skeletal shadows or inexplicable drafts—they are terrifying not because they are monsters, but because they are intruders in a territory Indy is sworn to protect. The sound design mirrors this isolation; human dialogue is often muffled or non-specific, prioritizing the wet crunch of leaves, the whistle of the wind, and the ragged breathing of Indy’s owner, Todd (Shane Jensen).

The narrative creates a dual track of horror. On the surface, there is a literal haunting—a malevolent force in the woods that seems to have claimed Todd’s grandfather and now hungers for Todd. But the deeper, more corrosive horror is the biological reality of Todd’s lung disease. To Indy, the "monster" and the illness are indistinguishable. The entity that drags Todd into the darkness is a heartbreaking metaphor for the inevitable slide toward death that no amount of barking or loyalty can halt. Shane Jensen delivers a largely physical performance, his deterioration observed in the periphery, which makes his moments of affection toward Indy feel like tragic goodbyes.

What separates *Good Boy* from its peers is its refusal to anthropomorphize its protagonist in the Disney sense. Indy does not have a sarcastic internal monologue; he does not solve puzzles with human logic. He reacts with the confusion and instinct of an animal. This narrative discipline pays off in the third act, particularly during a sequence involving a basement door that serves as a barrier between life and the unknown. The film posits that the greatest terror isn't the ghost in the machine, but the closed door we cannot open.

Ultimately, *Good Boy* is a triumph of empathetic cinema. It suggests that the ghosts we fear are often just the shadows cast by our own mortality, seen by the only witnesses who will never judge us for dying. It is a small film with a massive heart, proving that sometimes the most human stories are told by those who aren't human at all.