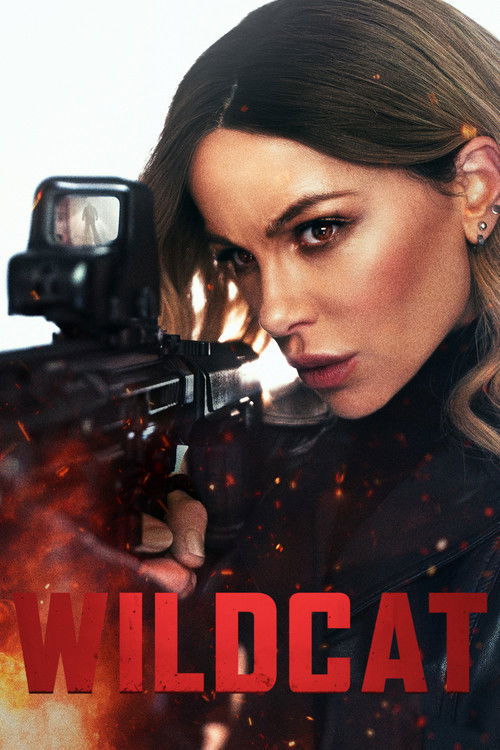

The Weight of SilenceIn the chaotic architecture of modern action cinema, silence is a structural weakness. We are accustomed to films that shout—through exposition, through relentless score, through the deafening machinery of franchise-building. Yet, James Nunn’s *Wildcat* (2025), a film that ostensibly markets itself on the kinetic prowess of Kate Beckinsale, finds its most profound footing when it dares to stop moving. Nunn, a director who carved a niche for himself with the technical bravado of the "one-shot" gimmick in his previous works, here attempts something riskier: a synthesis of high-octane kinetics and the heavy, humid atmosphere of regret. It is a film that asks not just how a weapon is fired, but what it costs the soul to pull the trigger one last time.

Visually, Nunn has graduated from the gimmickry of continuous takes to a more mature, if occasionally erratic, visual language. The camera in *Wildcat* is less an observer and more an accomplice, prowling the neon-soaked arteries of East London with a predatory grace. There is a specific texture to this film—a grimy, tactile reality that feels suffocatingly close. The widely discussed "car park sequence" is a masterclass in this philosophy. Unlike the clean, balletic violence of the *John Wick* era, Nunn shoots this brawl with a messy, desperate intimacy. The camera shakes not to hide the choreography, but to mimic the physiological panic of the characters. When Beckinsale’s Ada is cornered between concrete pillars, the lighting shifts from clinical fluorescent to a bruised purple, externalizing her internal bruising. It is a world where the shadows are heavy enough to crush you.

However, the film’s narrative engine often sputters under the weight of its own ambition. The script attempts to weave a Guy Ritchie-esque tapestry of Cockney gangsters and eccentric villains—Alice Krige and Charles Dance chew the scenery with delightful, if misplaced, theatricality—but this often clashes with the somber tone of Ada’s personal journey. The central conflict is ostensibly about a heist to save a daughter, a trope as old as the genre itself. Yet, Beckinsale elevates this material through a performance of weary restraint. She plays Ada not as a superheroine, but as a woman eroding. Her chemistry with Lewis Tan (Roman) is not built on sparks, but on the shared exhaustion of two people who have seen too much blood. There is a scene in a safehouse, quiet and devoid of music, where they simply share a look across a table; in that silence, we understand a decade of history that the script wisely leaves unspoken.

Ultimately, *Wildcat* is a film at war with itself, torn between the commercial demand for noise and the director’s instinct for visual storytelling. It is imperfect, jagged, and occasionally frustrating. Yet, in an era of polished, algorithm-friendly blockbusters, its roughness feels like a pulse. Nunn demonstrates that action cinema can still be a vehicle for human frailty, even if the vehicle itself has a few dents. It may not be a masterpiece of the genre, but it is a fierce, snarling reminder that even in the most formulaic stories, there is room for a little wildness.