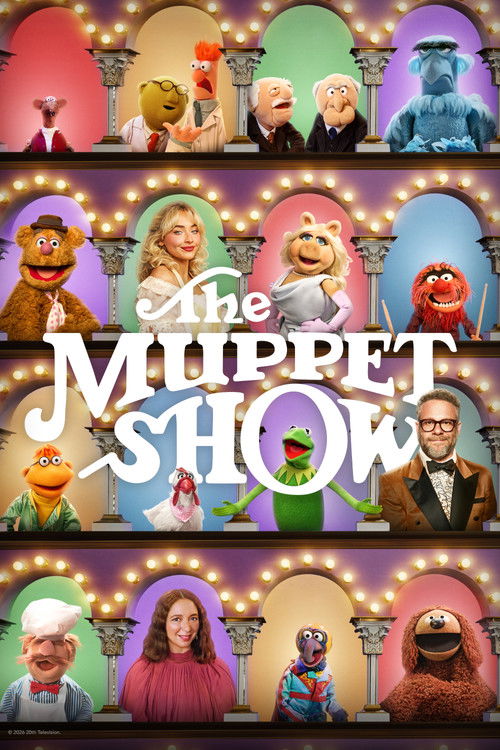

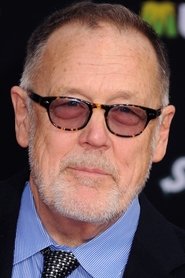

The Architecture of JoyFor the better part of two decades, the stewardship of Jim Henson’s creations has been defined by a persistent, anxious question: "How do we fix the Muppets?" Since the Disney acquisition, Kermit and company have been thrust into reality TV parodies, YouTube-style shorts, and cynical office sitcoms, each iteration straining to update a sensibility that was never meant to be modern. The profound relief of the 2026 special, simply titled *The Muppet Show*, is that director Alex Timbers and executive producers Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg have finally realized the answer was never to bring the Muppets into our world. The answer was to let us back into theirs.

Timbers, a director best known for the kinetic, maximalist stage productions of *Moulin Rouge!* and *Beetlejuice*, is an inspired choice for this material. Unlike previous directors who shot the puppets with the flat, sterile lighting of single-camera television, Timbers understands that the Muppets are creatures of the proscenium. He treats the Muppet Theatre not as a set, but as a cathedral of vaudeville. The camera moves with a theatrical fluidity, respecting the geography of the stage and the frenetic energy of the wings. When Kermit flips the switch to illuminate the dusty, dormant theater in the opening moments, it is not merely a plot point; it is a statement of intent. The film grain is gone, replaced by a rich, saturated palette that makes the felt textures look tactile, almost vulnerable.

The narrative framework is refreshingly slight: the show is overbooked, chaos is imminent, and acts must be cut. This allows the film to bypass the tedious character deconstruction of the 2015 ABC series and return to the core dynamic of the franchise: the desperate attempt to maintain order in a universe governed by entropy.

The guest star has always been the barometer for a Muppet production’s success, and Sabrina Carpenter proves to be a formidable straight woman to the madness. There is a specific alchemy required to share the screen with a pig in a wig; one must be famous enough to be recognized, yet humble enough to be upstaged by a prawn. Carpenter commits to the bit with a "gameness" that recalls the best guests of the 1970s—Alice Cooper or Rita Moreno.

In a standout sequence, Carpenter sings "Manchild" while engaging in a barroom brawl with a troupe of rowdy, intoxicated puppets. It is a moment of pure physical comedy that works because it refuses to wink at the audience. The film does not ask us to find it "cute" that the puppets are fighting; it asks us to accept the violent absurdity of the situation as the baseline reality.

Ultimately, this special succeeds because it rejects the cynicism of the modern era. In a media landscape obsessed with lore, universe-building, and "edgy" reinvention, *The Muppet Show* offers something radical: sincerity. It posits that there is still value in a frog with a banjo and a bear with bad jokes. It suggests that the warmth of these characters is not a resource to be mined, but a fire to be tended. By looking backward, Timbers has charted the only viable path forward. The lights are back on in the theater, and for the first time in years, the house feels like home.