The Hollow KingIt is a rare feat in cinema for a sequel to not merely continue a story, but to actively dismantle the romanticism of its predecessor. If *The Godfather* (1972) was a tragedy about a reluctant son saving his family, *The Godfather Part II* (1974) is a colder, more ruthless autopsy of what "saving the family" actually costs. Francis Ford Coppola, working with a freedom few directors ever achieve, constructed a dual narrative that functions less like a movie and more like a moral accounting ledger. On one side, we have the rise of a dynasty; on the other, its spiritual liquidation.

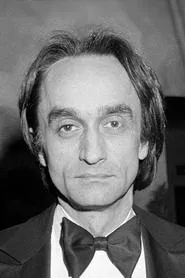

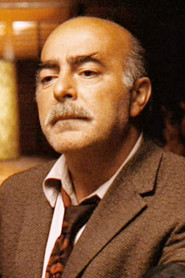

Coppola and cinematographer Gordon Willis delineate these two timelines with a visual language that borders on the subconscious. The flashbacks to young Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro) in 1910s New York are bathed in a golden, sepia warmth. These scenes—the stealing of a rug, the pear given as a gift, the murder of the local tyrant Don Fanucci—feel like folklore. They possess a tactile, community-driven nobility. Vito builds a criminal empire, yes, but he does so by weaving himself into the fabric of his neighborhood. He is a provider, a man who offers protection in a lawless world.

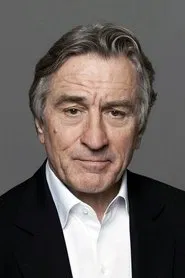

Contrast this with the timeline of his son, Michael (Al Pacino), in the late 1950s. The warmth is gone, replaced by the frigid greys of Lake Tahoe and the humid, sickly neon of pre-revolution Cuba. Willis captures Michael in shadows that seem to be swallowing him whole. Al Pacino gives a performance of terrifying restraint; he is a black hole of charisma, drawing everyone in and crushing them. While Vito’s violence was often personal and warm-blooded, Michael’s is corporate and reptilian. He commands death from behind a desk, sanitizing the blood with lawyers and senators.

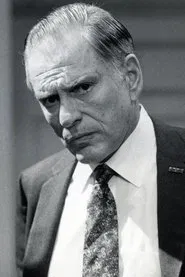

The film's central tragedy is that Michael succeeds in every metric where a businessman might fail, yet fails in every metric where a human being must succeed. He expands into Las Vegas and Havana, he outmaneuvers federal witnesses, and he secures his financial legacy. But the "family" he claims to protect is systematically purged by his own paranoia.

This spiritual rot culminates in the film’s most devastating sequence: the New Year’s Eve party in Havana. Amidst the chaos of a government collapsing, Michael grabs his brother Fredo by the head and delivers the kiss of death: "I know it was you, Fredo. You broke my heart." It is a moment of Shakespearean magnitude, signaling the final severance of Michael's soul. He is no longer a brother; he is purely the Don. The execution of Fredo later in the film—a lonely act on a grey lake—is perhaps the quietest, loudest murder in film history. It is the death of Michael’s last tether to his own humanity.

In the final reckoning, *The Godfather Part II* is a film about the terrifying isolation of absolute power. The closing shot creates a haunting rhyme with the film's flashback structure. We see Michael sitting alone on a park bench in the autumn of his life, a hollow shell of a man. The camera lingers on his eyes—dead, cold, and utterly victorious. He has won the world, but in the process, he has become a ghost in his own life. It is a masterpiece that reminds us that the American Dream, when pursued without limits, can become an American Nightmare.