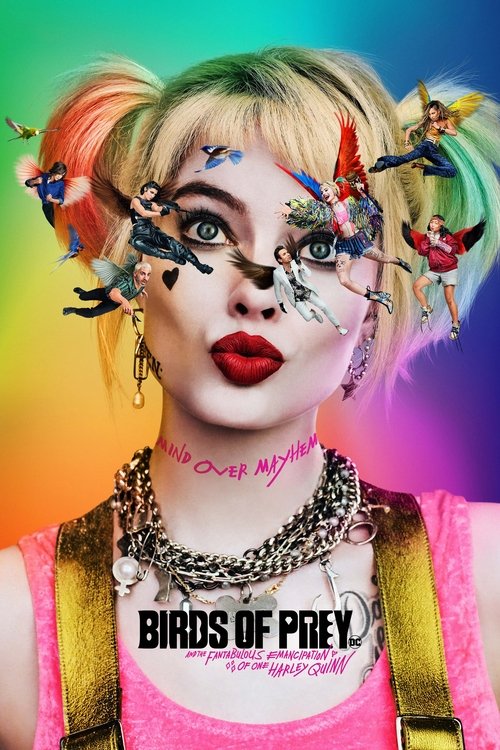

The Glitter and the Grit: A Technicolor Breakup LetterIn the vast, often gray assembly line of modern superhero cinema, where the stakes are invariably the total annihilation of the universe, Cathy Yan’s *Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn)* dares to ask a much smaller, more human question: Can a woman survive a bad breakup without burning the city down? Well, perhaps she has to burn a *little* bit of it down. This film is not a "product" designed to set up the next decade of franchise installments; it is a chaotic, singular piece of pop art that functions less like a comic book movie and more like a punk-rock anthem played on a calliope.

Yan, moving from the indie sensibilities of *Dead Pigs* to the blockbuster machine, refuses to play by the established rules of the "sullen superhero" aesthetic. Visually, the film is a rejection of the murky, desaturated palettes that plagued its predecessor, *Suicide Squad*. Instead, Yan and cinematographer Matthew Libatique paint Gotham in neon pinks, bruised purples, andcaution-tape yellows. The violence here is not grim; it is acrobatic and almost slapstick. When Harley Quinn raids a police station, she doesn’t fire bullets; she fires beanbags that explode into clouds of blue and pink glitter. This is a crucial distinction in the film’s visual language: it reframes violence not as a tool of masculine domination, but as an expression of feminine chaos. The "lens" here is distinctly female—the camera does not leer at the characters’ bodies, but rather admires their costumes, their athleticism, and their sheer, unadulterated messy energy.

At the heart of this phantasmagoria is Margot Robbie’s Harley Quinn, a performance of remarkable physical comedy and tragic undertones. Robbie understands that Harley is not merely "crazy" for the sake of edginess; she is a woman untethered. The narrative engine is not a glowing sky-beam device, but Harley’s desperate, manic quest for a bodega egg sandwich—a symbol of the small, normal comforts she craves amidst the wreckage of her life with the Joker. The film treats her emancipation not as a sudden girl-boss victory, but as a sloppy, painful process of identity formation. She is joined by a coterie of equally broken women—the rage-fueled Huntress (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) and the reluctant Black Canary (Jurnee Smollett)—who are not banding together out of altruism, but out of necessary survival against the suffocating narcissism of the villain, Roman Sionis (Ewan McGregor).

Ultimately, *Birds of Prey* feels like a correction to a genre that often forgets the humanity of its antiheroes. It posits that "emancipation" is not about becoming a perfect hero, but about owning one's own mess. The film’s nonlinear structure, mirroring Harley’s scattered psyche, might have alienated general audiences seeking a standard A-to-B plot, leading to its "underdog" status at the box office. Yet, looking back, it stands as a vibrant, defiant scream of a movie. It asserts that a woman’s value is not defined by who she dates, nor by whom she saves, but by the glorious, glittering chaos she chooses to unleash on her own terms.