✦ AI-generated review

The Weight of a Silent Promise

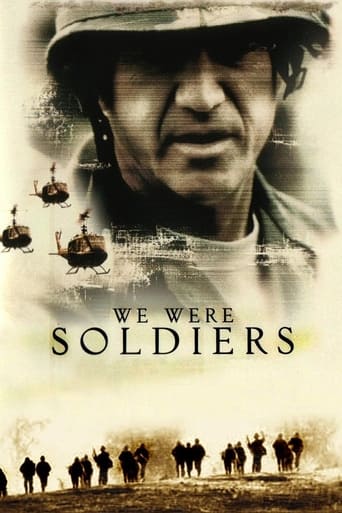

If cinema has taught us anything about Guy Ritchie, it is that he is a director of kinetic noise. His career is built on the manic rhythm of Cockney gangsters, rapid-fire dialogue, and editing that moves at the speed of a cocaine heartbeat. Yet, in *Guy Ritchie’s The Covenant* (2023), the filmmaker does something radically unexpected: he stops the clock. He trades the pub for the vast, unforgiving vacuum of the Afghan mountains, and replaces the stylistic swagger of *Snatch* with a brooding, dusty solemnity. The result is not just a departure; it is a maturation—a film less interested in the mechanics of violence than in the suffocating architecture of debt.

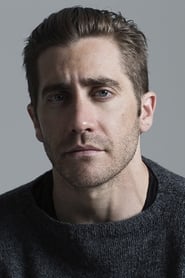

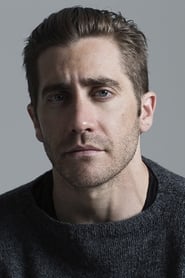

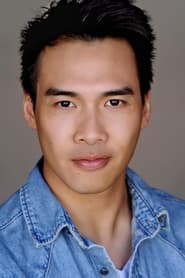

The narrative premise is deceptively simple, bordering on the archaic structure of a Western. U.S. Army Sergeant John Kinley (Jake Gyllenhaal) runs a unit hunting IEDs; Ahmed (Dar Salim) is the local interpreter assigned to his team. When an ambush leaves Kinley critically wounded and deep behind enemy lines, Ahmed drags him—literally and spiritually—across miles of Taliban-controlled terrain to safety.

Visually, the film is a game of two halves, cleaved by a central act of grueling survival. Ritchie’s lens, usually so restless, settles into a patient, observant gaze during the middle section of the film. We watch the excruciating physical labor of Ahmed hauling a delirious American soldier over rocky passes. There is no stylistic trickery here, only the raw weight of a human body and the terrifying silence of a landscape where every shadow could be a death sentence. The cinematography emphasizes isolation; the vastness of the environment makes the two men look like ants struggling against fate. It is in these wordless sequences that the film finds its pulse, stripping away the "war movie" veneer to reveal a story about human endurance.

The heart of the film, however, beats in the chest of Dar Salim’s Ahmed. In a genre that frequently reduces local interpreters to plot devices or tragic victims, Salim commands the screen with a stoic, dangerous intelligence. He corrects Kinley early on: "I am an interpreter, not a translator." He reads the room, not just the language. Salim’s performance is one of controlled power; he is a man who has swallowed his trauma to focus on the task at hand. When the roles reverse and Kinley returns home, Gyllenhaal delivers a portrayal of PTSD that is less about flashbacks and more about a spiritual haunting. He is alive, breathing air he hasn't paid for, and the "covenant" of the title transforms from a military agreement into a crushing moral obligation. Kinley isn't returning to Afghanistan to be a hero; he is going back because he cannot live with the ghost of his own survival.

There are moments where Ritchie cannot help himself—the final act descends into a more conventional shootout that feels slightly at odds with the intimate tension that preceded it. Yet, even amidst the gunfire, the film remains anchored by the gaze shared between Gyllenhaal and Salim. This is not a buddy comedy or a tale of friendship in the traditional sense; it is a study of a transactional bond forged in blood that becomes sacred.

*The Covenant* is a film about the failure of institutions and the endurance of individual honor. It suggests that when governments renege on their promises and bureaucracies fail to protect the vulnerable, the only thing left holding the world together is the word of one man to another. It is a muscular, empathetic piece of cinema that proves Guy Ritchie can do more than entertain; he can make us feel the heavy, jagged cost of a life saved.