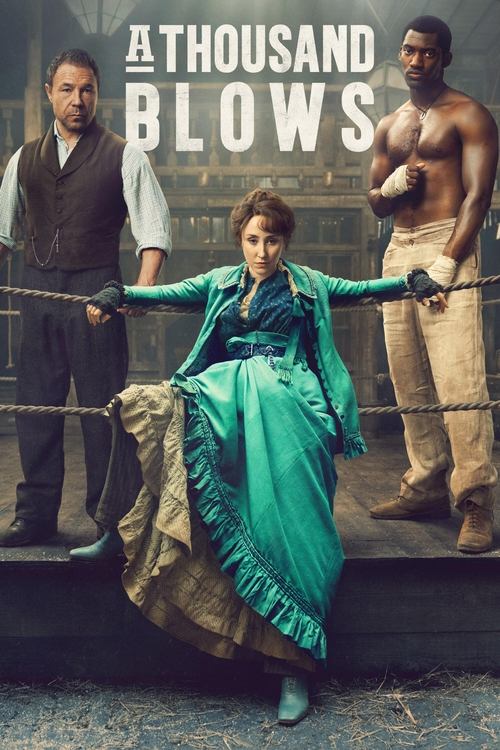

The Architecture of BruisesIn the modern lexicon of television, Steven Knight has become the architect of a very specific kind of British mythology: soot-stained, stylishly violent, and obsessed with the cost of ambition. If *Peaky Blinders* was an operatic saga of a family trying to buy their way into legitimacy, his latest offering, *A Thousand Blows*, is a far more guttural beast. It strips away the three-piece suits and the slow-motion swagger to reveal the raw, tender meat underneath. Set in 1880s Victorian London, this is not a show about men who run the world; it is about the men and women the world is trying to crush, and the violence they trade to stay upright.

The visual language of *A Thousand Blows* is suffocatingly tactile. Where other period dramas might romanticize the fog of London, here the atmosphere is thick with industrial runoff and human sweat. The camera lingers on the physicality of the East End—the mud that clings to boots, the blood that stains the floorboards of the illegal boxing dens, and the claustrophobic shadows of the alleyways. It is a sensory assault that mirrors the internal state of its characters. This is a world where the body is the primary currency. If you cannot fight, you cannot eat; if you cannot steal, you cannot survive. The aesthetic is not just "gritty" for the sake of genre; it creates a landscape where danger is the only constant.

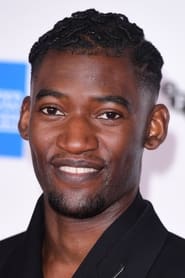

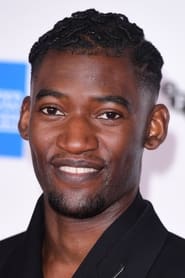

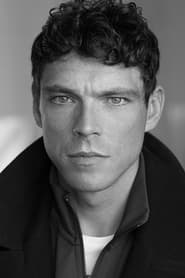

At the center of this maelstrom is Hezekiah Moscow, played with a simmering, soulful intensity by Malachi Kirby. Hezekiah arrives from Jamaica not as a warrior, but as a dreamer—hopeful for a career as a lion tamer. The crushing of that dream is the show’s inciting spiritual injury, forcing him into the orbit of Sugar Goodson (Stephen Graham). Graham, physically transformed into a slab of coiled muscle and rage, delivers a performance that is terrifying in its silence. Sugar is the old guard, a bare-knuckle king whose violence is a language he speaks fluently because he knows no other. The tension between Hezekiah’s reluctant lethality and Sugar’s desperate dominance forms the show’s spine. It is a clash not just of fists, but of eras—the "savage" immigrant narrative imposed by the British Empire colliding with the white working-class fear of obsolescence.

Yet, the show’s most electrifying current runs through Mary Carr (Erin Doherty) and the Forty Elephants. In a genre often criticized for sidelining women to the role of weeping wives or tragic victims, the Forty Elephants—an all-female gang of organized thieves—smash through the screen with jagged agency. Doherty’s Mary is sharp, pragmatic, and ruthless. The scenes depicting the gang’s operations are choreographed with the precision of a heist film, providing a sharp counterpoint to the chaotic brutality of the boxing ring. These women weaponize the very invisibility society imposes on them, turning their skirts and corsets into tools of theft. It is a brilliant subversion of Victorian gender norms.

The series excels when it juxtaposes these two worlds: the blunt trauma of the ring and the surgical precision of the street theft. One scene, involving Sugar Goodson casually breaking a man's hand with his own head, encapsulates the show’s philosophy: survival here is not about following the Queensberry rules; it is about being harder than the object striking you. However, the narrative occasionally threatens to buckle under the weight of its own grimness. There are moments where the relentless misery feels almost punitive, risking desensitization. But Knight and his team pull back just enough, allowing moments of genuine camaraderie between Hezekiah and his friend Alec to pierce the gloom.

Ultimately, *A Thousand Blows* is a muscular addition to the canon of London historical dramas. It lacks the mythical, almost comic-book sheen of *Peaky Blinders*, but it replaces it with something heavier and perhaps more honest. It posits that in the heart of the Empire, the most violent battles weren't fought on distant frontiers, but in the mud of the East End, for the price of a loaf of bread or a moment of dignity. It is a bruising watch, but a necessary one, reminding us that history is often written in scars.