Aang (voice)

Zach Tyler Eisen

Aang (voice)

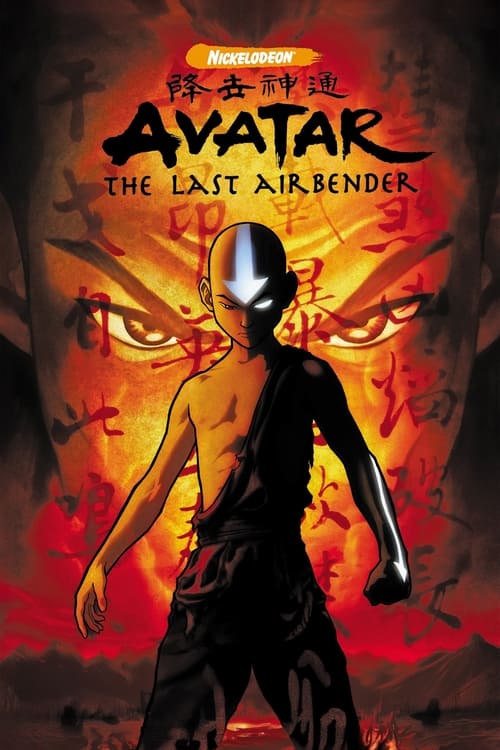

“Water. Earth. Fire. Air.”

In a war-torn world of elemental magic, a young boy reawakens to undertake a dangerous mystic quest to fulfill his destiny as the Avatar, and bring peace to the world.

Avatar The Last Airbender 15th Anniversary Trailer [4K]

Amazingly good and great and cool and....(ect)

Read full reviewStill holds up almost 20 years later. The animation is still so rich and impactful, and perfectly matched to the sound effects. Even the story and jokes hold up like a fine wine. It would make sense to reboot/remake this if it had aged poorly and needed a refresh, but why attempt to mimic perfection? The only acceptable remake I still hope for would be a 1:1 remake with even higher quality animation, but I don't think the industry has any intention of staying true to the original work with all these remakes. If only they might have the original thought of telling a different story inside the avatar universe, instead of trying to re-tell perfection with Aang's story.

Read full reviewJust watched the new Netflix adaption and it's ok, but just made me want to rewatch this!

Read full review"Avatar: The Last Airbender" Theme Song (HQ) | Episode Opening Credits | Nick Animation

More series you might want to watch next.