The Long Road HomeTo revisit *Smallville* today is to open a time capsule of early millennium anxieties and hopes, preserved in the amber glow of a Kansas sunset. Before the Marvel Cinematic Universe industrialized the superhero genre into a global export, and before Christopher Nolan turned the comic book movie into a grim treatise on terrorism, there was this sprawling, ten-year bildungsroman. Showrunners Alfred Gough and Miles Millar operated under a strict, now-legendary mandate: "No Tights, No Flights." This was not merely a budgetary restriction; it was a philosophical manifesto. By grounding the alien Kal-El in the mud and cornfields of the American Midwest, the series posited that the most interesting thing about Superman is not what he can do, but who he chooses to be.

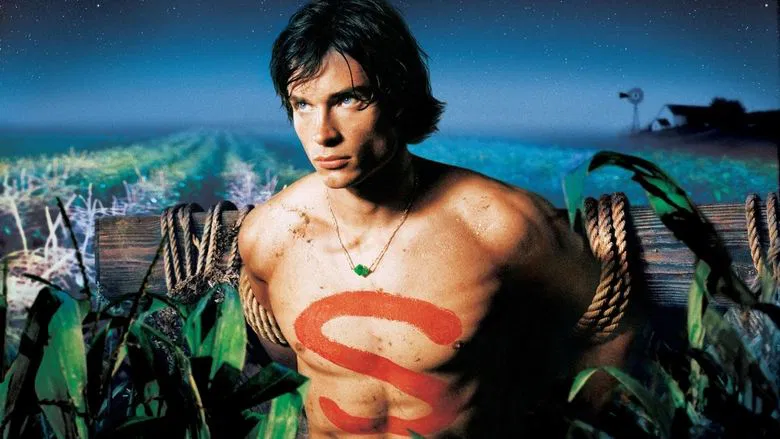

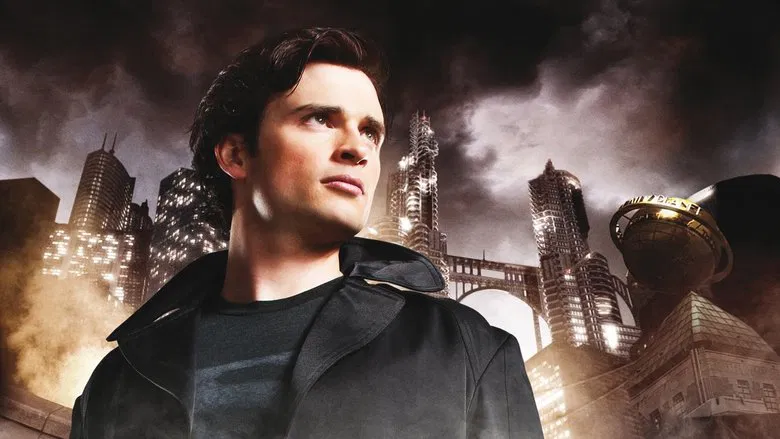

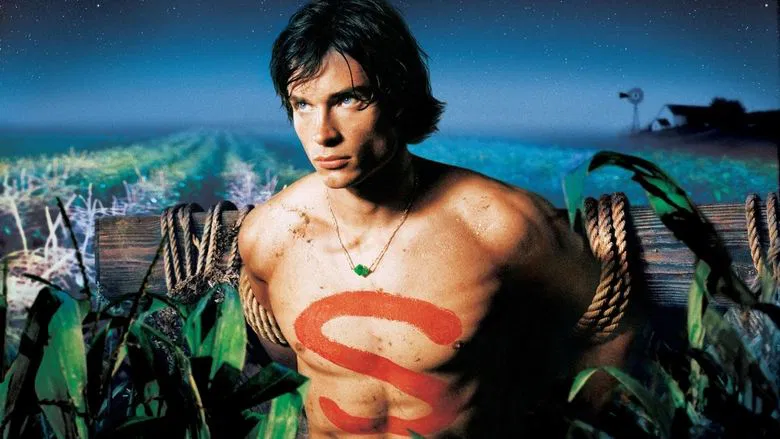

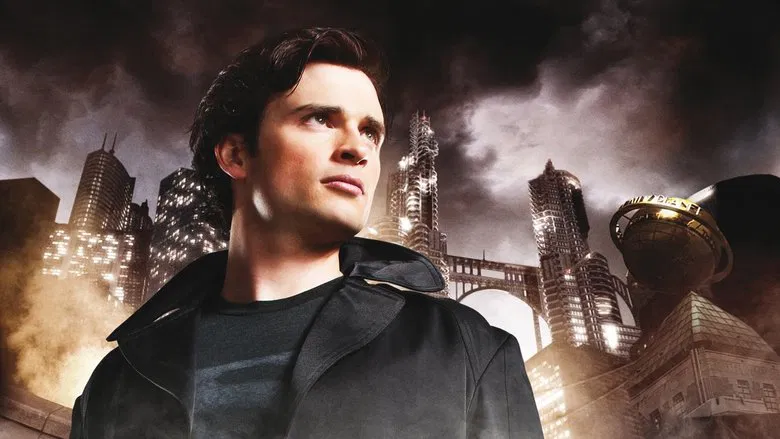

Visually, *Smallville* operates on a dichotomy of color that borders on the operatic. The early seasons are bathed in a perpetual "magic hour" gold—a deliberate evocation of Norman Rockwell’s Americana. The Kent farm is a sanctuary of warm earth tones, plaid shirts, and sunlight filtering through barn slats. This visual warmth stands in stark, violent contrast to the Luthor estate, which is rendered in cold blues, sterile grays, and shadows that seem to stretch longer than physics should allow. As the series progresses and the narrative center of gravity shifts from the farm to the sleek metropolis, the color palette cools, mirroring Clark’s loss of innocence. The "Freak of the Week" structure of the early years, often dismissed as filler, actually serves a crucial function: it builds a literal "Wall of Weird" that forces Clark to confront the unintended consequences of his mere existence.

However, the show’s enduring legacy lies not in its special effects or its monster-hunting procedurals, but in the Shakespearean tragedy at its core: the friendship between Clark Kent (Tom Welling) and Lex Luthor (Michael Rosenbaum). This is the engine that drives the series. We watch with the painful foreknowledge of history as two lonely young men find solace in one another, only to be torn apart by their fathers' legacies. Welling plays Clark with a stoic, burdened empathy—a god terrified of breaking the world. But it is Rosenbaum who steals the show. His Lex is not born a villain; he is a desperate soul clawing for redemption, slowly suffocated by his father’s cruelty and Clark’s necessary lies. The tragedy isn't that they become enemies; the tragedy is how desperately they wanted to remain brothers.

Ultimately, *Smallville* is a story about the burden of destiny. It is a long, sometimes meandering, but deeply felt meditation on the difficulty of growing up. In an era where superheroes are often treated as "content" or "assets" to be managed, *Smallville* remembers the human heartbeat beneath the steel. It suggests that the suit doesn't make the hero; the long, painful years of choosing to be good, even when the world is dark, are what truly forge the Man of Steel. It remains the definitive superhero soap opera, a saga that taught a generation that even the strongest among us must first learn how to walk before they can fly.